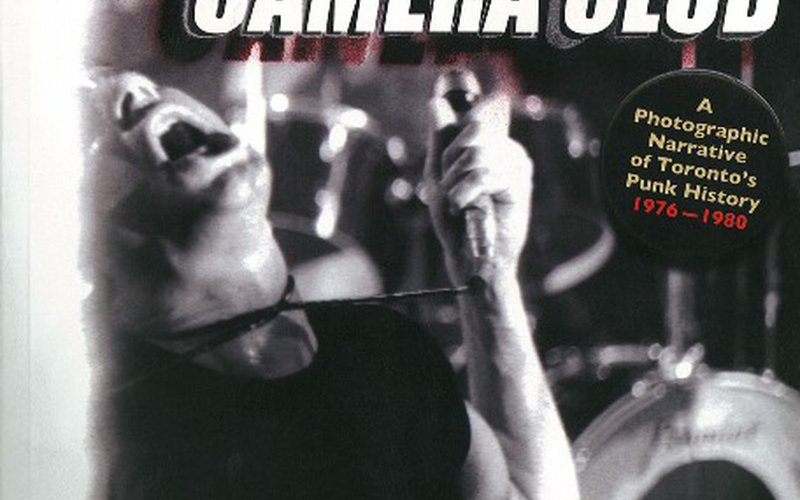

Before he played drums in Shadowy Men on a Shadowy Planet, before he composed the theme song for the US version of Queer As Folk, before he engineered the Sadies’ excellent Internal Sounds, Toronto-based producer, musician, and artist Don Pyle was a fledgling photographer cutting his teeth in the early Canadian punk scene.

Don visits Seattle this week with his Out-of-Focus Talking Slideshow and a photo exhibition at Machine Head Brewery. In anticipation of his guest appearance on my show tonight at 9:00 PM, I asked Don to compile a special list of his Top 12 Essential Toronto Punk Punks. We’ll be playing his favorite songs by these bands (as well as some of the big-name acts he shot) and discussing his new book, Trouble in the Camera Club.

Don Pyle’s 12 Essential Toronto Punk Bands

| 12 | The Demics |

| 11 | The Ugly |

| 10 | Teenage Head |

| 9 | Zoom |

| 8 | Tyranna |

| 7 | The Viletones |

| 6 | The Dishes |

| 5 | The Poles |

| 4 | Simply Saucer |

| 3 | The Diodes |

| 2 | The Curse |

| 1 | The Mods |

Don presents his Out-of-Focus Talking Slideshow this Friday evening, September 26, at 7:30 pm and his pictures are hanging until Sunday, September 28. (And then it rolls down the I-5 to Portland the following week.) Read my very detailed Q&A with Don, including his insights into growing up queer in the early punk scene, after the jump.

KEXP: I didn’t recognize most of the bands in your Top 12 list. Do you think the early Toronto punk scene in particular, and Canadian punk in general, has gotten the due it deserves?

Don Pyle: Yes it has, particularly in the past few years. In Toronto, there’s my book Trouble in the Camera Club, Liz Worth’s oral history Treat Me Like Dirt, and Colin Brunton’s fantastic and extensively thorough documentary film The Last Pogo Jumps Again. Nationally, Sam Sutherland’s book Perfect Youth chronicles the first bands and scenes directly connected to punk in every province. Vancouver has its own feature doc, Bloodied but Unbowed, and labels like Ugly Pop and Other People’s Music have done tons of reissues, or first issue, of recordings that were never heard when the bands were still around.

Why it’s happening now is a mix of nostalgia, fear of death and the need to document history (particularly as first wave punks become senior citizens); a real curiosity from youth, historians and chroniclers who recognize this as one of a number of significant movements in music; and the rise of technology—specifically the internet and digital technology—and ways to capture and disburse information. The information about almost any band you could wonder about is there for the asking.

So much about what was amazing about any local scene (and this is the case at any point in time, not just punk) was your entire experience: how old you were, who your friends were, seeing the bands live in particular places, what people wore or how much fun you had. All of that forms your perception about how “great” any band was. There’s tons of documentation about the second- and third- and fifth-rate bands but the best stuff is known. While the details are all important, every bigger city had many bands that were much more about a small number of people’s interest. They already know or can find out what they want to know.

Unfortunately, in Canada, a lot of the recordings left behind are demos or rough tapes, rehearsal tapes because there just wasn’t the infrastructure or interest at the time. You look at the UK and there are endless numbers of major and small labels that released a great wealth of high quality recordings. A city like Vancouver was lucky to have one label, Quintessence Records, which resulted in that city having great documentation about what happened there. Few other cities or towns in Canada had that level of interest or financial ability, so the support for bands then and the recordings they left behind are spotty.

Which came first (for you), the camera or the punk rock?

I had a camera from age four, before I had any records, a red 127 hand-me-down Brownie that I used to take pictures of my family, pets and Mr. Nemenyi, the teacher I had a crush on. Then a couple of cheap point and shoot plastic 126 cartridge cameras, the last of which I used to take photos of Todd Rundgren and Rush (debuting their 2112 album!) at Massey Hall, and the Ramones’ first appearance in Toronto in 1976. I bought my first 35mm SLR camera in 1977, before the Ramones’ second appearance at the New Yorker. To me, the Kodak Instamatic 104 camera is 1976 punk, the Canon AT-1 is 1977 punk. I never really thought of myself as a photographer, but more as someone who took pictures, so the camera came first but punk rock was more consuming.

How did teachers and your fellow students involved in the photography club feel about your subject matter?In retrospect, I think it’s quite curious and interesting that the three boys and the one teacher who were the camera club were all gay. The other two guys and I were friends and they came to some of the first show with me, and the teacher who ran it was very supportive and encouraging about anything that we found interesting to shoot. He encouraged taking lots of pictures and trying things out. Because part of our shooting was for the yearbook, he was concerned about quality so his focus was more on us knowing details about the technical process, like how to properly mix and use photo fluids, and ways to use and experiment with enlargers. From what I remember, he encouraged experimentation, but not in the way that has resulted in teachers not being allowed to be alone in a darkroom with a boy.

Were there any particular photographers you were aware of and sought to emulate?

Who I was first aware of was Mick Rock, because I thought he had a cool name and he was shooting David Bowie and Lou Reed. I knew Bob Gruen and Leee Black Childers because of their photos in Rock Scene, one of the few mags showing the new bands I was interested and curious about. My interest was way less about their photographic technique than about who they were photographing, what was projected by the subject, and the worlds of possibility shown—so different from my Toronto teenage reality. Robert Mapplethorpe was probably the first photographer I had a sense of as an artist, and largely because of the cover of [Patti Smith’s] Horses. I also went through a teenage Ansel Adams obsession. I am still quite awestruck by his work, Mapplethorpe less so. Photography was mostly connected to and a way to access the aesthetics of art in relation to music. It was and still is all part of a continuing process of identifying and decoding what makes the photo—the subject or the photographer, or some other factor.

There’s been some good discussion about the early London, New York, and Los Angeles punk scenes and their points of intersection (and disconnection) with the LGBT community. How gay-friendly was the Toronto punk scene?

It started as being very gay friendly, even though the gay visibility I saw both excited and scared me. The only visible gays were in the artier side of the scene, the bands and people for who punk and new wave was just an extension and continuation of the glam and trash of Bowie, Roxy Music ,and John Waters. The Dishes, the Biffs, Drastic Measures, Rough Trade, Oh! Those Pants, the Doncasters and a few others had really faggy/dykey sensibilities in lyrics, fashion, and clever kitschy presentations. All those bands were really connected to the Ontario College of Art and none were heavy like the all-straight Viletones, Diodes, The Ugly or Teenage Head.

The art/gay bands, particularly the Dishes, had a very strong connection to art collective General Idea. CEAC (Centre for Experimental Art and Communication), who provided the space to the Diodes to run the first punk club in Toronto (and Canada as far as I know) was co-run by gays. One of the first venues was David’s, a gay bar and dance club that hosted punk shows on a regular basis but with very little crossover of audience. And art galleries with a very gay presence, like A Space, also hosted some of the earliest shows of this revolution, like the first Talking Heads show when they were still a three-piece.

In the beginning, before lines were drawn and sides were taken, it was all considered to be “punk” but when the perception of “punk” changed to mean only the fast, heavy, loud bands, it alienated the gays who had for a short time been such a huge influence on the blossoming of this scene. The shift that occurred during 1978 left a scene that was very alienating to a young gay boy but totally stimulating and exciting to a young music freak excited by revolutionary ideas and extreme volume. The gay very quickly separated from punk.

You describe yourself on the Trouble in the Camera Club website as "shy" teenager. How did you go about approaching your subjects? Are there any musicians who were especially helpful or encouraging about you as a junior shutterbug? Any shots you still can't believe you got, even to this day?Shyness is in many ways another word for insecure. I had come from a pretty damaged home-life situation, had very thick glasses and really bad eyesight, had this big secret (being gay) that meant you had to be aware at all times of many things most people take for granted, and was a kid entering the adult world of bars and live music so there was a lot to have insecurities, feel uncertain, or be shy about.

There really wasn’t much approaching the bands I photographed because they were on stage, I was in the audience. I just did it. As time passed, I made more and more friends - many of them pictured in my book - and became friends with many people in local bands because they were out at the same shows and also the audience. Few things help you get over being shy than getting contact lenses and being in a band so when I started doing that, it was another step in building my confidence. Sometimes I’d give bands a few prints I’d shot, and photos I took of The Mods’ first show resulted in them being the first people I didn’t knowing hiring me to take photos.

Freddy Pompeii of the Viletones and his partner Margarita ran a punk shop and they encouraged me to print photos that they could display in the store, but I wouldn’t say there was that much active encouragement from musicians. Encouragement came much more from my couple of other friends also taking photos because at the time, they might have been the only ones seeing most of my photos. It was easy to feel that people didn’t really care because mostly they were “just” local bands, bands no one outside of this relatively small scene cared or knew about.

I have maybe ten shots I am in awe of and that I know I’d love if someone else had shot them. Some of my faves are Teenage Head’s Frankie Venom, on his knees, his mascaraed eyes rolling up in a beautifully lit and focused photo. I recall him even saying ‘Wow’ when I gave him a copy of it. It really captured him at the peak of his greatness as a performer and Head as a band. Another is a profile shot of the Ramones on stage at the New Yorker theatre, with Dee Dee in the foreground, Joey and Johnny in a line behind him. There is so much thrust and action in the picture and only Dee Dee’s face is visible, and even it only partially, obscured by his super cool haircut. Some of my Viletones photos capture just how volatile and exciting they were, I have several of them that are just amazing.

One photo that really struck me and that I only discovered for the first time just as I was putting the book together is one I took of me against my bedroom door. It’s covered with flyers and I have tape X’s over my eyes! I had no memory of taking the picture, so it was like coming face-to-face with myself through some kind of time dimension twist.

How did photography influence your musicianship?

With each year that passes, I feel like I perceive more and more things and details that are happening in my older photos. One particular thing is self-consciousness. I see that so much in the photos of people at their youngest, as they too entered the world of adults and are on their own path of self-discovery. Seeing that self-consciousness helps me see how ridiculous and narcissistic it was and helps me let go of self-consciousness more and more as a player.

I also sometimes think of particular visual archetypes when I’m playing or writing music; that a particular body shape or pose indicates a particular rhythm, or that a specific look has a specific sound attached to it. With work and play I’ve done in still photography, moving pictures, music writing and playing, and sound recording and mixing, I’ve developed more and more understanding and perception that those things are all the same. Sound and color and light all operate on frequencies that have exact relationships to each other so quite often a photograph will have a particular sound to me, one that I can sometimes, when things align in some magical way, articulate when I play or write music. I can sometimes make a sound that is the same as what I see in a picture.

Earlier this season, KEXP asked: "Who are your Favorite Artists of All Time?" Listen in throughout the Fall Fundraising Drive, September 26th through October 3rd, to hear which artists your fellow members of the KEXP Community voted for! KEXP DJs piped in with their own Top 12 lists, which we'll be…

Did you ever wish you could enjoy doughnuts all day long—even while working out at the gym—and still look fantastic? Now you can … when you donate to KEXP’s Fall Fundraising Drive!

KEXP wants to know: "Who are your Favorite Artists of All Time?" Pick out a dozen musicians, bands, projects, and share them with us before Friday, September 19th at 6:00 PM PST. And then tune in during KEXP’s Fall Fundraising Drive, September 26th through October 3rd, to hear which artists your fe…