The sun is starting to set, turning the sky an icy pink and blue as I walk down the quiet street of Spítalastígur in Reykjavik, Iceland. In this tranquil moment, I start to hear a rumbling in the distance. Crashes of cymbals, the thump of a bass drum, and the rattle of a snare. As I turn right onto Ingólfstræti, I’m pretty confident I know where the clamor is coming from.

Tucked behind one of the aluminum-sided homes, I arrive at R6013 – a basement venue and hub for some of Iceland’s emerging DIY (Do It Yourself) scene and artists. The descending stairway entrance is modest, marked only by a wood plank with the venue’s name nestled next to jars of cigarette butts.

Walking inside, I find Æger Bjarnason sitting at the drumkit with his eyes close, rapt in his playing. He’s alone in the space and doesn’t seem to notice my presence right away. I stand at the opposite end of the narrow room and watch him play, both of us in a sort of trance. When he comes to a natural stopping point, he looks up and finally sees he’s not alone and quietly raises from his drum throne to greet me.

This basement is part of Bjarnason’s family home. Not only does he host shows with local Reykjavik bands, but the place functions as a sort of headquarters for his label Why not? Plötuútgáfa!.

“I just prefer the doing to the talking,” Bjarnason says as we sit on a couch in the back of the room. “I've learned that by just doing a lot of cool things people will actually take notice.”

What Bjarnason is describing is essentially the ethos and thesis of DIY. It’s something he came to naturally. Bjarnason is a prolific musician himself, playing in groups like World Narcosis and powerviolence outfit Dead Herring. He’s been performing music since he was a teenager and initially expelled immense energy trying to get support for releases from his projects from labels. Frustrated by the time and effort it seemed to take, he opted to begin releasing his bands’ words on his own.

During a recording session with World Narcosis, he told the band’s recording engineer about all the releases he was working on. The engineer asked if he’d ever considered starting a label. He hadn’t, but the idea seemed so logical when presented to him.

“I figured since I was putting out music for more than one of my own bands, and since it was really only me doing that part of it, it easily made sense to pile that together,” he says. And thus, Why Not was born. The label primarily releases (but is not limited to) the “heavier” bands in Reykjavik, from the grindcore of bands like Grit Teeth to mesmerizing electronic experimentations of IDK IDA. The label’s catalog has continued to steadily grow since releasing their first World Narcosis 7-inch in 2011.

Releasing other bands’ music gave Bjarnason a chance the alleviate larger issues he saw afflicting artists in the Reykjavik scene. So often he’d see bands finish a record and spend a year shopping it around before it’d finally get a release. The whole time, the bands stay active, yet their material’s still in waiting. By the time a record gets a release, the band would already have moved on creatively.

“If it's a good record and the band is active, then that just kind of sells itself. It doesn't need six months to prepare for some sort of victory, although of course, it's helpful to have people helping you get the word out there,” he says.

Starting Why Not? was just one step in fixing what he saw as an issue afflicting active bands. But Bjarnasson still saw work to be done in Reykjavik. Alongside the label, he started R6013 around the same time.

As someone who began performing music at a young age in 2008, Bjarnasson cut his teeth playing in all ages spaces. He can recall being 14-years-old and frequenting punk shows packed with kids his same age. But by around 2010, those venues began to shutter or see a dramatic downturn in attendance. At this time he was about 16-years-old and was playing venues he wasn’t legally allowed to be in – primarily bars (Iceland’s drinking age is 20-years-old).

“It's not really about me not drinking, which I don't do, but it's always been really important to me that there is this space that is open to everyone,” Bjarnason says. “And I think that's really important for a scene to grow and to keep going because there has to be a way in, especially for younger people.”

This mindset is what prompted Bjarnasson to convert his basement into the house venue it is today.

My chat with Bjarnason wasn’t my first time stepping foot in R6013. I found my way to the venue the night before after being tipped off by Skátar’s Benedikt ReyNisson who has assisted KEXP over the years during our Iceland Airwaves Festival broadcasts. During the thick of the festival, I had no shortage of live music options to choose from. But when I tell ReyNisson that I’m curious to find some of “Iceland’s underground,” he insists I make the time to go to a show at R6013.

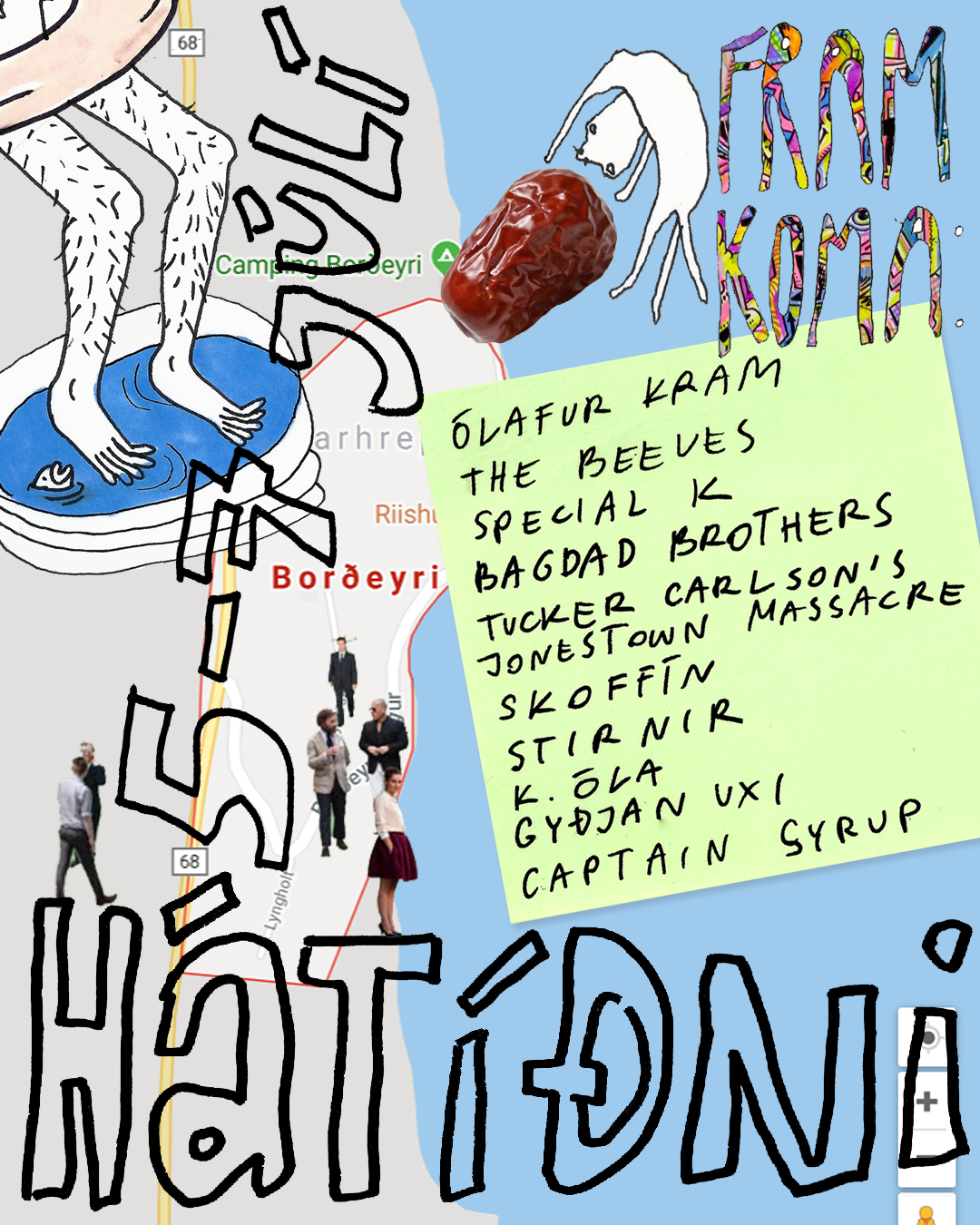

Before every show at R6013, Bjarnason paints the show’s lineup on a large wooden board in bright, eye-grabbing colors. In lieu of using stencils are a defined template, the painting is done freehand. There’s a charm to it that aligns not just with the DIY ethos of R6013, but the larger concept of DIY that’s permeated for generations of underground music fans.

You can feel that the painting is done by a fallible human, advertising a show of fellow humans who are making music happen with whatever’s at their disposal. Without having to put the words on the sign, it almost seems to say, “We are doing this and so can you.” It’s the first thing I see when walking up to the show, glowing like a rainbow beacon in the dark of night.

There’s always a bit of trepidation when walking into a stranger’s home, even with publically advertised house shows. But R6013 couldn’t be more welcoming. A large pot of vegan stew simmers in the corner and I’m offered a bowl before I can even sit down.

Rows of worn out couches sit in the back of the room, staggered in height as-if in a theatre. If I reached up while standing flat-footed on the ground, I’m pretty sure I can touch the ceiling. A smattering of setlists is posted up with electrical tape on a section of the south-facing wall.

Rugs are scattered on the floor, leading the short distance to the opposite side of the room where a drum kit, stacks up amplifiers, guitars, and pedals reside. I’m told that behind the black curtains surrounding the performance area are mattresses that are made available for touring bands who may need a place to crash.

Near the door, there’s an old desk being used as a display for CDs, cassettes, vinyl, and zines – primarily featuring artists on Bjarnason’s Why Not? Records as well as releases from like-minded Reykjavik collective post-dreifing. The representation of these groups goes beyond merch as I notice Bjarnason lounging on the elevated couches with Bjarni Daniel, one of the founders of post-dreifing and the lead vocalist for the band Bagdad Brothers and who had just played KEXP’s broadcast from KEX Hostel days before.

As we all chat and commune over stew, more and more people trickle in from the cold. It doesn’t take too many people to pack the space up. Steadily, the room gets cozier and the chatter gets louder. The evening’s opening act Laura Secord casually make their way through the crowd, lead vocalist Alison MacNeil (formerly of the band kimono) has her young children in tow – all wearing ear protection. Bjarnason, it turns out, also drums for Laura Secord and takes his place behind the kit.

I’ve been to many house shows in my day, but the energy in R6013 is unlike anything I’ve experienced before. Without a raised stage, the band is level with the audience. Not just that, the venue encourages dispelling the boundaries between artist and audience. After entrancing the audience with the atmospheric intensity of their nameless first track, the band requested everyone come in closer – not just in front of them, but amongst the musicians.

When I chat with Bjarnason the next day, he tells me he’s often asked about putting a raised stage in the venue. Given the size of the venue, if 60 people show up it’s a packed house and can be hard to see if you’re standing in the back. But for Bjarnason, there’s bigger importance to keeping the performance area in the same space as the audience.

“I didn't want the separation between the band and people in the front,” Bjarnason says. “I wanted it to be more of an intimate interaction, which is too easily messed with by just putting the band slightly higher than everyone else. It just isn't the same.”

For Bjarnason, it’s not just about cultivating the environment and feel of the space, but a chance to make a point that there is no hierarchy between artist and audience.

“It's not really about being on the stage and performing like you're somehow different from the people that are on the floor in front of you,” he adds. “So having a space where there's no real divide between the band and the audience, and after the band plays they just hang around maybe, eat the same food that you eat and sit on the same sofa as you and watch the other bands, and everyone's just kind of in it together.”

It’s a sentiment that post-dreifing aligns with as well. In a Skype chat months later, I speak with aforementioned Bjarni Daniel and his fellow post-dreifing cohorts Valgerður Björnsdóttir, Dagur Kristinn Sigurðsson Björnsson, Aron Bjarklind, and Snæi Jack.

“We like to look at the audience as active participants in the scene,” Daniel says. “Every person who attends any event is as important to the event as any other person.”

While post-dreifing functions separately from R6013 and Why Not?, they carry the same banner of inclusion and equivalency in Reykjavik’s music scene.

Post-dreifing first came to be in the most Icelandic of settings – a Northern Lights museum. The museum was hosting a mini-festival event called A Lovely Great Time, bringing together some of Reykjavik’s disenfranchised musicians. Notably, the festival was organized by artists whom Daníel says were born around the year 2000.

Being surrounded by young people close to their age and expressing similar artistic and philosophical ideas, the idea of a collective became almost obvious. They’d take inspiration from Icelandic collective of the past like Smekkleysa (Bad Taste), whom notably broke artists like The Sugarcubes and Bjork. But they also took note of the work being done in Iceland’s burgeoning hip-hop scene which saw artists routinely collaborating and promoting each other’s music.

When I ask about DIY in Reykjavik, post-dreifing proposes another idea instead.

“I think we prefer ‘DIT’ – Do It Together. It's the same mentality because it's focused on the group effort,” Daníel says.

The name post-dreifing roughly translates to “post-distribution,” a quasi-mission statement as well as a commentary on the current music economy. In the era of the Internet and modern streaming services, what does it mean to put out a record in 2019? It’s why post-dreifing releases all of their artists’ albums for free on platforms like Bandcamp.

“Music has sort of become free in the last couple of years with the Internet and piracy and subscription-based music platforms,” Jack says. “It's basically free. So why try to like put up some kind of a paywall between the listener and the artists?”

Post-dreifing isn’t opposed to artists making money, of course. All of their releases are also available for a “pay-what-you-want” option on Bandcamp and they say they do see people opting to pay bands for their digital records. But the reasoning goes deeper than economics – it’s about accessibility.

“Everyone should be able to enjoy good music,” Björnsson says.

That idea is central to what post-dreifing is all about. Alongside releasing music from Icelandic groups like Daníel’s Bagdad Brothers, sideproject, stirnir, asdfhg., and numerous others, post-dreifing also puts on shows – often collaborating with Why Not? and R6013.

In January of 2017, Jack invited some friends for a quasi-mini-festival in the Borðeyri – one of the smallest towns in Iceland. Most of the potential audience didn’t think Jack was actually going to follow through with the idea, meaning mostly just artists showed up (it’s where Bagdad Brothers played their first show).

Post-dreifing appreciated what Jack was doing and offered to help, naming the festival Hátidni and moving it into the summer instead of winter. Hátidni officially emerged in 2018 and will return again on July 5 of this year. It’s a festival that post-dreifing says prioritizes visibility and sustainability over profit. Why Not’s Bjarnasson, who also helps organize the Nordanpaunk festival, is also helping with this year’s Hátidni.

Tickets for Hátidni are listed for 3.000 kr. (roughly $24 USD), but the collective makes note that no one will be turned away if they can’t afford to pay. The artists will perform in an old elementary school, which will also serve as sleeping corridors for artist and the post-dreifing members.

From the way they operate their fests and their distribution, it’s easy to infer the collective’s anti-capitalist slant. Or rather, pro-inclusion and pro-accessibility. It’s a marked and intentional reaction to the woes of the music industry that artists both in and outside of Reykjavik are coping with.

“What we want to do is try to in the long term create a platform alternative to the commercial music industry where it puts creativity first and not profits,” Daníel says. “The idea is to create a platform that in the long run would function as a sustainable place where people could just come with their project and help other people with their projects and the thing would just kind of grow.”

Post-dreifing may sound idealistic in their approach, but they are very much attuned to the reality of the financial costs that are inherent to creating and promoting a musical project. The collective offers to help cover costs for artists to see through their ideas. While most of their catalog is digital-only, they’re willing to share funds to help an artist do limited physical releases. They refuse to take a profit, only taking back the money they put into the release.

“In short, we have terrible business model,” Jack says.

Why Not?, R6013, and Post-dreifing are not the only groups in Iceland vouching for artists, but they’re all bringing in a youthful voice and perspective to Reykjavik’s arts scene. What they’re doing is more akin to public service than a business. It’s an emphasis on community and supporting ideas.

I think back about that Laura Secord show at R6013 often. I’d be remiss to say that I do find similar collectives and house venues in Seattle and other cities in the United States, all working for the common good of the arts. But being in that space is a reminder of why it’s important to keep these ideas alive, especially when it’s getting harder and harder to survive and sustain your ideas as an artist.

There was a point in Laura Secord’s set when someone accidentally bumped the light switch, leaving the whole room in complete darkness. The band was unfazed; completely entranced in their distorted, delightfully brooding sonic sprawl. The song came to a natural dramatic pause. In this small space of time, the bass player yelled for someone to turn on the lights. In a way that couldn’t possibly have been planned, someone flipped the switch back on in perfect time with the band coming back in.

It was a small moment, maybe inconsequential to the performance as a whole. But it was a small reminder of the community banding together; listening to what each other needs and breaking down the boundaries between audience and performer. When those expectations are shattered, you’re making room for something miraculous to happen.

DJ Kevin Cole chats with the father of the late Icelandic composer in Reykjavik

KEXP shares videos and reflections from a tribute to the late Icelandic composer, filmed during our 2018 trek to Reykjavik.

The newest act on our lineup performs a dreamy set of indie-pop from the KEX Hostel in Reykjavik.