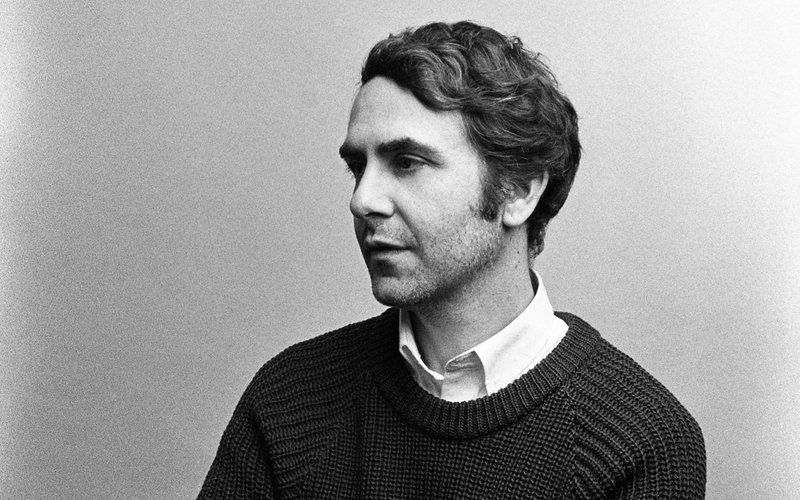

While most people use the cop-out of a self-titled album for their debut, it's taken California-based artist Chris Cohen until his third full-length for Captured Tracks Records. The album cover features Chris himself, staring stoically into the camera. It's not sadness in his eyes, nor is it anger — it's just Chris.

The time was right. Following 2012’s Overgrown Path and 2016’s As If Apart, Chris Cohen is his most overtly personal album yet. During the two years he wrote and recorded the release from his Lincoln Heights studio and at Tropico Beauties in Glendale, California, his parents got divorced after 53 years of marriage. As Cohen explains via a press release: "My father spent most of his life in the closet, hiding both his sexual identity and various drug addictions. For me it was like being relieved of a great burden, like my life could finally begin.”

Like his previous releases, Chris Cohen is a lush, intricate release with varied time structures, layers of instrumentation, and Cohen's soft, plaintive voice over the melancholy melodies, harkening back to the '70s-'80s era of music when his father worked as an entertainment and record company executive and the head of A&R for Columbia Records. Despite being literally face-forward on the album, it also features the most guest lyricists of a Chris Cohen release: Katy Davidson (Dear Nora), Luke Csehak (Happy Jawbone Family Band), and Zach Phillips. And in the middle of the album is a 6-minute traditional Scottish folk song titled “House Carpenter.”

As KEXP looks at the themes of addiction and recovery for Music Heals, we spoke with Cohen about the new album and his own personal journey as a child of an addict.

KEXP: The new album's been out for a couple of weeks now. How does it feel? Are you starting to get responses from people?

Chris Cohen: Yeah, I've gotten a lot of feedback from people and I'm grateful that people have listened to it. It's exciting to have a new record out and I just got back from a tour, so I was getting a lot of feedback from people and it's been very positive. It's nice.

Maybe it's because of what my songs are about, but a lot of people have come up to me who've had similar experiences and wanted to talk about it. And that feels pretty... it feels pretty raw. I'm not quite sure how to best respond to people that I don't know, who I meet at shows and they're telling me really heavy stuff. I mean, I guess I told people very heavy stuff in my songs, so, it seems appropriate. But yeah, I wasn't prepared for how to respond to somebody that's having a really hard time.

Has it been emotional? This album is so personal.

It's not that different than any other. I should say, having those kinds of conversations and doing interviews and stuff, that's the part that... I don't know if I feel “emotional” but I'm just trying to be as thoughtful as I can be about it. But the touring and all the rest of it, it's not actually that different. It's mostly about just doing the work of playing, and getting from place to place, and I'm not thinking so much about the emotional content of my lyrics except for when I'm singing really.

I should say, right now, myself, I'm not thinking about the things that I'm talking about in my songs. They're with me, but I'm probably not thinking about them as much as you might think. I put a lot of work into making the songs and then when I'm performing, you know, I'm thinking about the words, but it's a performance.

It's interesting because at the same time that this is kind of your most, at least, straightforwardly personal album, it's also the album that you've had the most guest songwriters. I wanted to ask you about your decision to have a bunch of guest songwriters on this album.

Partly it was a desire to balance out my perspective. I think I just had the sense that the people that I asked would bring something that was needed. And then choosing a traditional song with "House Carpenter" — I wanted something outside of my own world, but that was related. And I felt like everybody brought that. I just wanted the record to be a little bit more well-rounded.

Could you tell me more about how you feel like "House Carpenter" is sort of related to the themes on the album?

I'm not sure I actually thought about it in that way. I just really liked that song. The Watson Family record on Rounder Records is where I learned that song and I listened to that record a lot when I was younger. I think, I've found myself being a fool in a way that the sailor character in that song is a fool. He can only see things in terms of his own ego. He assumes it's about this other man who was a threat to his relationship. He doesn't even have a sense of what his partner gave up. His perspective is so selfish and small. There was something I felt was very lifelike in that. I think I've had foolish moments like that. I thought that was an interesting, very subtle, and very well-observed characterization.

If I understand correctly, from what I've read in the press release and some of your previous interviews, you didn't even really know what was going on with your dad at first?

I didn't know about my dad's addiction issues until I was 30-years-old, and I didn't know about his sexual identity until then. When I was 30, he let everybody know that he was going to rehab. He was addicted to crystal meth at the time and then it all started to come out. We all had a lot of questions and it gradually came out that he's gay and my parents have had an open marriage basically. When they were married, my mom understood that my dad was gay, and it was sort of like tacitly agreed to that he was going to be seeing men on the side. They were married in 1961, I think. They were 18 and 19 years old and they were married.

After my dad went through that first crystal meth problem, he went to the Betty Ford Center. And he was like, "I'm a totally new person now. I'm, like, Mr. Recovery." And he got really into recovery. He climbed the ranks of Narcotics Anonymous, and he became a leader, he was a sponsor, and he really learned how to game that system the way he learned how to game every other system. He was supposedly sober for 10 years. I'll never know if he really was. But he was using with people from his meetings, he was scoring at meetings, and stuff.

And then around 2014 or 15 or something, it was starting to become evident that something was going on. I think my mom had known for a while, but he had gotten into heroin and other stuff. I'll never know the whole picture but my dad basically... I think he felt like he was always in control, and he only really lost control because, my parents were pretty well off for a while and eventually their financial situation was such that he couldn't really maintain the illusion anymore. It was interesting how their finances were what really forced him out of hiding. And he was basically spending all of my mom's retirement. My mom was still working, he's retired. These are people in their 70s we're talking about. I'm still a little bit surprised that my dad would be doing that kind of thing at that age. And it just got to the point where she had to leave him. My mom was in denial for so long that it really took 'til she was literally about to lose everything that she had: her retirement, their home, and everything. She had to get out just in order to save herself.

So that was what eventually forced the end of this marriage. It wasn't as though she didn't know he was gay, or she didn't know about his addiction problems. It just reached the point where she had to get out to just save herself. So, me and my sister had been kind of living through all that.

I think unless a person is really willing to actually do recovery in a real way... There's a lot of people out there that I think have learned to game the recovery system. They've learned to like use recovery as sort of a shield, even if they're not using. I think that sometimes recovery can still allow people to not really deal with the real core issues that are probably driving their addiction. And so, my dad was something like that. He loves the language of recovery just as much as he loves addiction. I think he's still using. I don't speak to him anymore. I think he may still not be willing to face what's really going on.

I don't know if you've seen the movie Beautiful Boy or read the books by Nic and David Sheff that it's based on, and it’s obviously the reverse situation where the son is the one with the addictions, but he also goes to recovery and ends up scoring drugs and breaking his sobriety with other people in the group.

Yeah, I mean I definitely don't want to knock [recovery centers]. I just think it's down to the person, you know, whether you really are going to do it or not. I can always say for my dad, he didn't really do it. And he loved trying to get everybody to think that he did.

I've been to a couple of Al-Anon meetings. I think it just wasn't for me, but it really helped to me to go. Some of the ideas were very helpful. Like in particular, the idea that addiction is a social problem, it's not just a single person's problem.

I had to recognize that my whole life was formed around this addiction. I just wanted to think about all the different ramifications of that, just to understand myself better.

And going back to my lyric writing, that was something I was trying to think about a lot. I had to recognize that my whole life was formed around this addiction. I just wanted to think about all the different ramifications of that, just to understand myself better.

Like the lens of family members being in in this cycle around the addict and all of their different types of roles that they play in relation to the addict. I found those ideas from Al-Anon very helpful. I don't take them too literally but just the general idea has helped me a lot. I've seen all the ways that I've sort of formed around my dad but it's also helped me sort of differentiate the parts that aren't like that and sort of recognizing like, now I'm out of my dad's orbit. I don't have to continue. Those roles don't actually mean anything anymore to me.

There's a quote in my bio where I said something about feeling liberated or free or something. And that's what I was getting at. I just tried to step away from my dad's addiction and try to see like, "Okay, what else is there?" Because I'm not a child anymore. And I don't have to be part of that. I mean, I'll always be part of it, but some of those rules don't make sense anymore. I'm a pretty quiet person and I'm very shy. I don't know if there's like an archetypal name for this type of character in an addict's family, but I tend to withdraw and get really quiet and just sort of disappear. And I think that was my way of coping with my dad, but it doesn't make sense anymore. That isn't necessarily who I am. So, I found that those ideas liberating.

My dad has used words to control everybody and to shape his own reality so that he can keep using, and I'm mistrustful of words, I think for that reason. I think I've chosen music as my way to speak.

I mean, yeah, because on the album you're the exact opposite. You're not withdrawing, you're not disappearing, and you're not being quiet.

[laughing] That's true, you're right. But I never think of myself that way. I know what you're saying — that's true — but yeah, I think in everything I do, this idea of being quiet or something has stuck with me. I still think of myself as like, I'll talk when no one else is talking. And it's a big part of why I make music, too. My dad has used words to control everybody and to shape his own reality so that he can keep using, and I'm mistrustful of words, I think for that reason. I think I've chosen music as my way to speak. Pure music is easier for me to communicate in. I think I learned to play better than I learned to speak.

I think I would disagree with that. I find the lyrics very astute and very affecting.

Well, thank you. I mean, that's more of a struggle for me. I'm still trying to get comfortable with doing interviews, whereas if you put me in a drum set or give me an instrument or something… I learned to use music that way. Like music is my way into society. I feel like an outsider otherwise, and that was something that I wanted to address within my own music on this record. It was just something that I was thinking about while I was making this music.

I think that ties in perfectly with what KEXP's Music Heals program is, which is the whole sense that you're not alone because you can turn to music, whether you're creating it or listening to it or playing it or any of that. So, when you were growing up, I had read that you started to learn how to play drums at the age of three.

Well, my parents bought me a drum set when I was three. I don't know if I knew how to play, but I did play a lot. I don't know. I don't know if I know how to play now.

That's definitely not true. Even though you didn't know what was going on with your dad growing up, were you feeling like the unspoken tensions?

Oh, yeah.

During tough times, people turn to music for solace. Was that true for you growing up? Were there certain songs or bands that you would turn to and find solace in?

Oh, absolutely yeah. I think that's a big part of why I make music. I want to be part of that.

Yeah, just music in general. I guess it was something to escape into, but it was also a way to try to reach out, too. Music was important to my family. My dad worked in the music business. My mom was a singer when she was younger. She was a musical theater person. Then my sister played music also. And I learned that being a fan of music and playing music and listening to music was a way of participating and it was a way of trying to get some kind of real conversation going with my dad, which never ever really happened but...

I don't know if I would say there was certain music that I loved. When I was young, I just loved everything basically. Like when I was real little, it was listening to my Beatles cassette over and over again. And then it was sort of discovering like the music that my parents said was good, which was the Rolling Stones and The Who and Jimi Hendrix and stuff. And then I got really into punk music. I noticed that my dad didn't like punk music, and, you know, I constantly wanted to engage him on the discussion about punk music, I think. As I got older, I just learned more about how musical taste is sort of a way of communicating with other people. In our culture, it's a big part of your identity, and I think I was clued into that pretty young and so yeah, I don't know. Music in general was an avenue to participate in when whereas I felt like I couldn't participate otherwise kind of. I didn't play sports. You know I was quiet and weird and music was like, this is how I can be a part of the world.

What would you want to say to a KEXP listener or reader who has a parent or family member who's addicted to drugs?

I would say, make sure you have someone you can talk to who is not part of that immediate situation. Like, try to get some perspective. I've talked to other friends that have similar types of situations to mine, and I just always want to make sure that they know that I'm here if they want to talk about it.

And you don't have to continue this situation. You know, there's a boundary between you and your parent. And it's gonna be hard, but you can get out of there if you need to.

Every situation is so different. I don't know if my experience applies to lots of other family members with addiction. I mean, I actually had a pretty easy time eventually deciding how to approach it for myself. After so many decades of, what I would say, abuse, I guess, I was just like, I can't do this anymore. But it felt like a more hopeless situation for me. And I have other family members that I can I can turn to, so I’m lucky.

I think that we're dealing with a culture that been sick for a long time and continues to be sick. I don't want to defend addiction or something like that, but I do think that in my dad's case, a lot of cards were stacked against him by the culture he was in. And, you know, other people of his generation turned out better. I can't say why things happened the way they did with him. But my point is, I think we're dealing with cultural problems of many different kinds that are playing into gender roles, economical, racism, capitalism. Like all the other illnesses in our culture seem to play into this situation a lot.

So, it's given me it's given me a lot to think about. And I hope things get better.

Chris Cohen is out now via Captured Tracks. Chris plays Seattle on Friday, July 19th at the Sunset Tavern with Dear Nora.

Ahead of Music Heals: Addiction & Recovery, KEXP spoke with Patty Schemel about the impact of drug abuse on the Seattle music scene in the 90s, her personal journey, and the role that music continues to play in her recovery.

Ahead of Music Heals: Addiction & Recovery, KEXP spoke with IDLES guitarist Lee Kiernan, who celebrated seven years sober this April. In this exclusive interview, Lee shares his experience with addiction, and the role music has played in his journey to recovery.