KEXP DJ John Richards speaks with John King (a.k.a. King Gizmo) of The Dust Brothers about co-producing Beastie Boys’ seminal second album, Paul’s Boutique:

KEXP: Hey, is this John?

John King: Yes, it is.

This is also John. It’s John Richards from KEXP so this is going to be really confusing.

(laughs) Awesome.

Thanks for taking the time to do this with us.

No problem.

We’re talking to [Dust Brother] Mike [Simpson] on Monday, so you can just say all the great stuff and he’ll just fill in the blanks.

(laughs) Sounds good.

Where are you right now?

I’m, uh, in my in-laws’ garden in Portland, Oregon. (laughs)

That was going to be my guess. (laughs) I’ve been playing Paul’s Boutique for years now, and since we’re taking the time to break it down across a whole day, let’s start by talking a little bit about the Dust Brothers first. The amount of work that you’ve done, the number of artists you’ve worked with, is, as you know, really impressive. Tell me about where you guys, or you, in particular, started in music.

I started out playing my parents’ records and my grandparents’ records. My grandparents are from the deep South, specifically Panama City, Florida. I grew up listening to Johnny Cash and Chuck Berry – all kinds of stuff like that. And then I picked up the trumpet at my grandma’s house and I played for a long time, up until college. So I’m classically trained as a trumpeter. In high school, I started to get into punk rock in LA. I had some friends who got me into cool shows like Dead Kennedys, 45 Grave, X, Nina Hagen. In college, I met some guys that introduced me into the funk and dance scene. When I was discovering these rap records – because there weren’t that many back in the early ‘80s – I instantly loved it and sort of grew along with the rap scene as it came out to the west coast. I met Mike, my partner in the Dust Brothers because I was doing a funk radio show at KSPC in Claremont.

Me and Mike had mutual friends, so it was a pretty stoney, music-loving crew there out there in Claremont. My friend who was the music director knew Mike, who had done a rap show before I did my funk show, and he had just graduated, so I think he thought he had to quit. So we hooked up and ate a lot of Doritos and just started sharing our love of rap. We started doing a show together called The Big Beat Showcase. That’s kinda when things started to really happen. We had a huge audience with phones ringing off the hook. The studio had those little lights that went up like a tower next to the board and they were fully lit up during our show.

Were there other hip-hop shows happening in the area?

I feel like we were the first. And even the local station that started to play rap in LA, KDAY, I don’t think was playing rap at that point. Mostly because there weren’t that many rap records at the time. Part of our show was that whenever a rap record would actually come out, we would play, like, every song on the record because we had a three-hour show. It was nothing like today where there’s a million rap songs. Each rap record that came out was like a glorious gem.

Do you remember the first time you heard a rap record? Or the first record you searched for that really had that impact on you to love rap?

The first one I probably heard was probably "Rapper’s Delight." And since I was on the west coast, I wasn’t really at the epicenter of what was going on in hip hop. A record had to be pretty big for it to make it out to the west coast. One of my earliest rap memories was UTFO’s first record. It was really fun, but those aren’t even necessarily my favorite early rap records. That would change as I grew to have more knowledge and taste for rap.

Tell me about when you transitioned from doing the radio show into doing production. It’s amazing that it was Tone Loc who first heard you and asked you to produce some records.

Mike and I were trying to do production for our radio show. We were into DJing because that was just part of the culture of early hip hop. We really wanted to do these amazing megamixes where we’d take the instrumental from one funk song and combine it with an acapella from a rap record, or put two instrumentals together on top of each other. Later, this would be called mashup, but not during our heyday. These mixes were really inspired by this record from New York called Scratchmasters and, from when I was younger, a record called “Mr. Jaws”. The guy who made it took all these pop records and turned it into a novelty comedy record mashed up with a guy talking about the shark from them movie. To make these tracks, we borrowed our friend’s four-track machine so that we didn’t have to be the ultimate DJ wizards, even though Mike was very good at DJing and I was working at it. With the four-track, we could do multiple takes and lay stuff down and make these production-quality mixes that we would then play on our show. We were really proud of them. I eventually bought an eight-track reel-to-reel machine, and we started to make even more advanced megamixes. We thought these were like the greatest things ever. It was like a precursor to what we would do later on in our professional production. All of that led up to Tone Loc coming into the studio. When we played him some of the stuff we’d been doing for the radio, which was just backing tracks for voiceovers at the time, he really liked it and wanted us to come meet the guys who were about to start Delicious Vinyl.

The story goes that Tone Loc heard you and you ended up working on a single for Young MC?

Young MC wasn’t in the picture yet; that would come later. A lot of rappers would come to the show because it was a big radio station. It was actually a big punk radio station. It played a lot of now-seminal punk and alternative music in the ‘80s. The show was kind of like a one-of-a-kind place, so when Ice T had a new record, he would come down and we’d have him on the show. Local talent would come down too. These kids were amazing. Super authentic, real kids from a genre that was just blowing up.

So the show was pretty big, but it sounds like you guys had some pretty loose rules? Did you have to deal with the FCC? As a fellow radio guy, I’m curious about that. We’ve had a hip-hop show running here – the longest in the city – for decades and we have similar stories about local artists. You must have just been blown away with the amount of talent and the freedom on the radio waves.

(laughs) Our freedom was basically just our lack of honor for the rules. We played curse words, we played east coast rap that had curse words. Like Eazy E’s “Boyz in the Hood”. We played that like crazy. I mean, we couldn’t not play it when the phones were lit up with kids requesting “Boyz in the Hood,” because that song was just real. The kids could relate to it. I mean, it was coming from a SoCal neighborhood – how could they not relate to it?

Seriously! So when did you first meet the Beastie Boys? What was your first encounter with those guys?

I was working on some music that was probably going to be Dust Brothers music on that 8-track machine at the apartment of Matt Dike, who did Paul’s Boutique with us. He was one of the cofounders of Delicious Vinyl. Matt was a guy who had run a popular underground club night called Power Tools, so the Beasties knew him from that. So Mike D just stopped by out of the blue. Matt probably knew he was coming by but didn’t tell me. (laughs) I was a huge Beastie Boys fan. I just loved the total sonic landscape of Licensed to Ill. The drum machines and the record cuts that were on the record were so cool. So Mike D stops by, and me and Matt start hunting for various drugs so that we could all hang out and have a good time. And Matt slyly popped in a cassette of Mike and I’s work. Matt and been helping some on the music, but it was mostly Mike and I working on songs for a possible Dust Brothers album. So we were all in Matt’s kitchen and Mike D heard the tape and asked what it was. And Matt said very coolly, “Oh, you know. Just something that we’re messing around with or whatever”. And Mike D goes “can I buy that?” (laughs). And Matt played it off, but after Mike D left, we freaked out and made a demo for them to listen to on cassette, which was the medium of the day, and customized it to make it more like what we thought would be good for them, which was partially based on our style and partially based on Licensed to Ill. So we sent them to the demo, and I was so desperate to hear back. I asked Matt about it every day for like two weeks: “Did they call? Did they hear it?” And one day, we got a call. It was the Beasties asking if we could come into the studio that weekend and record two songs. So we went in and we did “Shake Your Rump” and one other song. Ii can’t remember which one it was now. That was the first time we were in a real studio. Before that, we were DIY, using an IBM PC to control and a sampler with, like, four seconds of memory. And, of course, two turntables. So being in a real studio was a real shock to us. We didn’t know what to do with that stuff. So we were laying down our tracks and looping them and cutting and scratching one track at a time.

Did you play it off like you knew exactly what to do when you got in there?

Oh no. It wasn’t a professional-type relationship. We were kids. it was all about having fun and being cool and loving music.

So you’re in Matt’s kitchen on drugs with Mike D.

(laughs) Well, not right then. We were just prepping it for when he arrived.

You know, at that time, the Beasties were very commercially successful, but some people looked at them as juvenile or a fluke. but you really loved Licensed to Ill.

To me, it’s like iconic sound. You’re just going to hear it and think, “that’s foundational iconic hip hop.” Now, “Fight for your Right (to Party)” doesn’t enter that equation. (laughs) But the 808 drums, and the cuts, and using Zeppelin drums and riffs (vocalizes riffs) – to me, it was all what makes up part of the foundation of ‘80s rap.

Definitely. As far as seminal records go, you can look at others from the era, and hear many of those same sounds. I remember getting that record because of “Fight For Your Right (To Party)”, which, like millions of others, was like my gateway drug to the Beasties and then I immediately gravitated to the other songs on the album. I’d never heard anything like it. And I heard other bands and didn’t understand how I could hear their music sampled in another song. And that took me down the road to Paul’s Boutique. For kids who wanted “Fight For Your Right (to Party)”, this record was not that. At all. So you guys had these early versions of tracks that you were gearing towards the Beasties, but when did they decide to talk to you about going full-on and working with you for the whole record?

I don’t feel like there was much of a conversation. I think they knew that we wanted to work with them. By the time we were really working with them, we’d been involved with hit records like Tone Loc’s, so we actually had some things going on, but we certainly felt like we weren’t really in the music business and that the Beastie Boys were bringing on nobodies. But we definitely felt like we were doing really cool stuff and innovative work. At the same time, we were aspiring to do music like the Bomb Squad, Boogie Down Productions’ first album, and EPMD. We wanted to do stuff like all the rap music we loved, but we also felt original and innovative in the way that we were doing it. Right after we did those first two songs, we went to a Run-DMC show at the Greek, and in the middle of the show the Beasties went onstage and performed the two songs we’d just done. I was in the audience, and that was just the most amazing moment for me. “Shake Your Rump” came on and the crowd was just going insane. It was just an amazing feeling to see the crowd react to those songs being performed. I don’t really know when we had a moment where it was like “we’re really doing the whole album”. It was just a relationship that came about organically. We were really happy to be doing that album.

Just to get your opinion on us breaking down the album, a year ago – which was Paul’s Boutique’s 25th anniversary – I’d broken down the references in LCD Soundsystem’s “All My Friends” and that seemed like a challenge. One day, somebody suggested breaking down a whole record, and Paul’s Boutique immediately jumped out. so we’re playing every song on it. What do you think about that?

I love it. I mean, we put way more than 12 hours into the album and we felt like it was an amazing work of art and that it was meant to be listened to carefully. When it came out, it didn’t do well commercially, so that kind of put a damper on things. But it’s been wonderful hearing people tell us they appreciate it over the years and it almost takes me back to where I was when I finished it and thought it was the greatest thing ever.

Did your success with other avenues make you question your vision for the record? How did you guys feel about the path you went down?

We felt held back by the Beastie Boys to make something with hits on it. They had a desire to do something super artistic and cool, and anytime we tried to move in with a track that sounded like it could be a hit, it would get rejected. I mean, we wanted it to flow and be great, but also have a hit. The Beasties could have totally made a hit song, and we could have too. But they didn’t want to make one.

So what was their response to the album? They must have been totally fine any which way, no matter how it did.

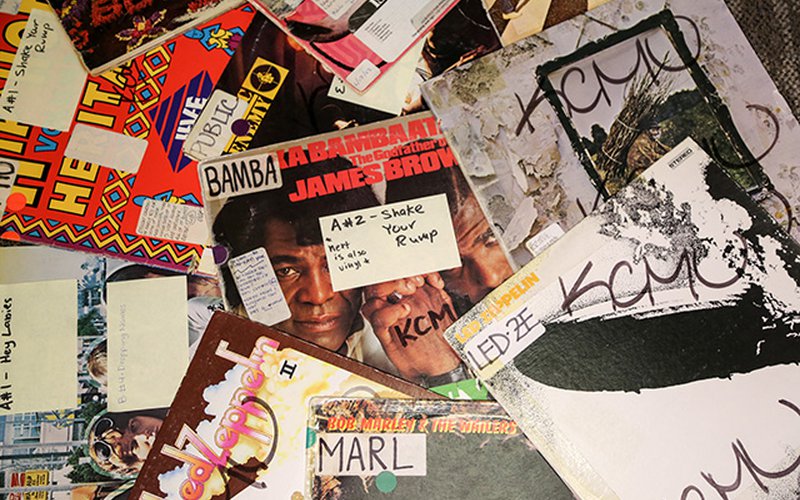

Yauch wanted the album – and this was extremely disappointing to us – to be the cool album that people would just discover in used or cutout vinyl stores. He just had this artistic desire that combined with his love for crate-digging and how it inspired him. I think he wanted this album to be something like that. Maybe it was even a reaction to their commercial success with “Fight for Your Right (to Party)”.

He kinda got his wish, didn’t he?

He did. And it turned out to be great for them. It was a good feather in our cap as well. We’re very proud of it, but it was disappointing at the time. We really wanted to make a hit with them.

I think people would look at it the other way around, with the producer pushing for artistic stuff and the artist not. That is fascinating. While we’re on the topic of Adam, we want to dedicate this day to him. I’m sure it was sad when you heard of his passing.

Yeah. He was the most involved with us on that record, from our perspective. He moved into the building we lived in, which was in a crappy neighborhood, and it was a crappy apartment. He would take us skiing because we didn’t have any money. We just musically worked really hard together on the record. He was our closest co-worker on that record.

And, from all reports, a beautiful human being as well.

Yeah.

You’ve produced everything from Beck to Hansen to Linkin Park to the scores for Fight Club and Muppets from Space. Where does Paul’s Boutique stand with the rest of your discography?

Well, it was a one-of-a-kind experience. It was fun for us because it was rap, and it was also big because it gave us our footing in the creative music business. That was a rap record that was really special, and the artists went on to cement their place in history. Although, for me, they were already there because of Licensed To Ill. After that, we got shifted more into alternative and pop. I did a contemporary folk album with Steve Earle not too long ago. We’ve done all kinds of things, but Paul’s Boutique is really special because it was one of our first works and also because it was full of music that was going to be the original Dust Brothers album.

Do you have a favorite track from the album?

(long pause) I just love the whole album. I will say that “Shake Your Rump” is really special in the way that it was put together, and the way that it would be played when I would go into an underground club.

As far as samples go, were there any that you just had to get in? Or one you couldn’t believe made the cut?

Well, part of the way that we did things was that not only would you get inspired by other works, but you would also begin to love other songs because of their use in other rap songs. Working on that record sent me even deeper into crate-digging and made me really appreciate a lot of music from the early ‘70s and late ‘60s. You would learn about an amazing bass player or arranger and look him up and go digging even deeper. That album was a labor of love: we loved everything in it, and it was so meticulous. I was so anal about everything being perfect, especially the small details and transitions, so I really love it all.