"I remember you was conflicted, misusing your influence - sometimes I did the same."

"I remember you was conflicted, misusing your influence - sometimes I did the same."Kendrick Lamar dug himself a bit of a hole on his explosive 2012 breakthrough LP, good kid, m.A.A.d city. His problem? He's a fantastic storyteller. Actually, he's likely one of the best we've ever had. In two and a half years, his "short film" album has transformed the face of the mainstream hip-hop game, with its incredibly vivid true-to-life moments, its personalization, and an unbeatable west coast cadence that felt like it had been gone for the better part of a decade. But it's not the stories Kendrick tells that are the problem - those stories are his life, his dreams, and his ongoing discoveries, put to verse. Rather, it's what the stories mean to Kendrick now, and moreover, what they mean to the millions of fans of all backgrounds and walks of life that listen to his music. With good kid, m.A.A.d city, Kendrick built himself a house, and on each of these walls is cleanly projected a separate story, a separate anecdote of himself cleanly mixed and mastered and spun and streamed in just the right light to sell you one dimension, one dimension and no more. You watch the video for "Backseat Freestyle" and you get Compton Kendrick turned up to full blast with a black and white video shot with 90s camerawork and a post-production dustiness to make it look gritty. But with "Bitch Don't Kill My Vibe", you get the smooth, conscious Kendrick, removed from Compton context in the California hills, or at a funeral, introverted, trying to explore the thoughts in his head before betting lost in them, wondering what it all means. And if, God forbid, ever the two shall mix (like on the video for "Poetic Justice") there's a big warning label across the screen telling you not to take it all literally.It's these stories that got Kendrick's foot in the door. They got Kendrick a Grammy nomination and countless award show appearances. They had him topping every festival list for two summers and counting. And the takings didn't stop with good kid, m.A.A.d city - Kendrick scored two Grammy wins for "i" and is headed into another festival season at the top of the food chain. So what's the problem here? What's wrong with embracing the fruits of hard labor? God knows everybody else is excited to hear him sing "I love myself". And yet, it's that top line we hear almost a dozen times on his good kid follow up, this week's already legendary To Pimp A Butterfly. Why is Kendrick conflicted? Why does he continuously criticize himself as a leader, as a brother, as a son, and as a human being? Why is he calling himself a hypocrite in the wake Trayvon Martin's death? Isn't this guy supposed to be Compton's human sacrifice? Isn't he the one bringing the city back to the world?

The questions posed here are bigger than Kendrick. In fact, as he learns throughout To Pimp A Butterfly, they are questions even bigger than his biggest heroes. Kendrick is learning how much a dollar costs in his industry. He is learning what it means to make a dollar the way he does, learning about its implications across the board, and trying to reconcile that to himself without going insane under the bright lights shining down upon him. But the way Kendrick has captured his struggle here on this record is a gift. It's an opportunity for every listener to understand the world Kendrick lives in. Not the one painted in perfectly isolated shades of black that's sold to you by promoters waiting for a paycheck - the one that weighs on his brain every day and waits for him to make a change. As he echoes the words of his grandmother on the record, "Shit don't change until you get up and wash your ass". If good kid, m.A.A.d city was Kendrick's conversion, To Pimp A Butterfly is his baptism. Kendrick is washing himself clean of any doubt or inner conflict, but the road to truly loving himself is complicated.

Kendrick isn't shy about his biggest hero. If you didn't catch it from the countless subtle references throughout the record or the sampled real-life interview that ends the record, it's Tupac. The influence of the west coast hip-hop legend is extremely evident throughout Kendrick's music, from the unabashed accounts of gangster epics to the understand and encouragement to others offered openhandedly. But on To Pimp A Butterly, Kendrick is ready to explore another dimension of knowing his hero. In particular, he's becoming him. Kendrick isn't doing this by osmosis or emulation - he just understands who and what he is. At this point, Kendrick is as his hero was in his day (try and picture him without twenty years of ripening legacy), plus, he's older than Tupac ever got to be. Thus, listening back to the old interviews like the one used on his record, Kendrick is listening to Pac in a different light. He's not looking for a word of encouragement or a perspective to possess on his own. He's trying to get advice from a brother in the same place about what to do with all his power and his influence. So why ask? Well, let's start at the beginning.

To Pimp A Butterfly starts exactly where good kid left off. Coming off the victory lap Dre feature of "Compton", Kendrick is high on life and has dollar signs in his eyes. "Wesley's Theory" is 100% desire, 0% reality, all spread over a Funkadelic infused track with a George Clinton solo so nasty that it crowds up the mix about half the time. Kendrick names off every single thing he can think of to spend his newfound cash on. He did the work and now he's getting the credit - in his own words, "married to the game and the bad bitch chose". But even still, there's a wariness. After all, Wesley Snipes did three years for tax evasion. Kendrick realizes that making money's one thing, but keeping it is an entirely separate ordeal. So Kendrick gets frugal on "For Free?", letting a million and one thoughts go about where he's from and where he's headed over a bullet train of a jazz track. Hood dreams are out the door - from here, it's up and out and headed towards the sun. And why not? Kendrick is a king and he knows it. On "King Kunta", he throws shade on everyone that's ever doubted, running full speed ahead and knocking everyone trying to take his legs out from under him. Kendrick has the yams (could be a nod to the Invisible Man or Things Fall Apart) and he's not letting go.

But there's a dark side to all of this. Kendrick realizes that in the struggle to the top, he's isolated himself, and something's been lost in translation between the good kid and the platinum record status. On "Institutionalized", Kendrick realizes that all this newfound perspective on belonging - all this getting used to award shows and flashy watches and the whole nine yards - it isn't shared. He might have traded in hood dreams for the big time, but he can't superimpose his new horizons on others, especially those who come from the same mad city. Didn't he get to anyone when he sang about the dangers of money trees for shade? Well, maybe they can't hear him. Maybe the walls he's built around him are too thick. "If these walls could talk they'd tell me to swim good", Kendrick raps on the next track. This line could go a million directions. "These walls" are his new walls - the walls of the industry, of King Kendrick in his castle. "These walls" are telling him to swim in those "Swimming Pools" that got him where he is, enjoy the benefits of his royalty, and play into it because that's all the people want to consume: a separation of desire and reality, Wesley's theory at its finest. Meanwhile, the walls around his family and friends and his hometown look entirely different. "If your walls could talk, they'd tell you it's too late, your destiny accepted, your fate." Kendrick paints a vivid picture of a prison cell, a charge of accessory and no vindication to speak of. Meanwhile, Kendrick is living the dream, making money off selling the culture that puts childhood friends in prison and gets them shot by cops, and sleeping with their ex girl while they are serving a sentence.

Now we see where the misuse of influence starts to take hold, and turn into self-loathing. On "u", we see an entirely different relationship with self than "i". "Where is the influence you speak of? You preached in front of 100,000 but never reached them", he screams into the mirror. More so than simply abusing influence, Kendrick has lost himself because the reality of the dream is nothing like he thought it would be. In his head, Kendrick has two options: play the game and pimp the Compton butterfly until it's dead, or go back to being a caterpillar. Avoiding the issue, Kendrick turns to distraction, and the frugality of "For Free?" turns to willful spending on "For Sale?". The sweetness of the yams personify into Lucy, a temptress who meets all of Kendrick's needs and asks for nothing but cooperation in return - no thought, just cold, dead cooperation. No longer the pimp, Kendrick realizes he might be the prostitute after all.

Facing the reality of it all, Kendrick decides to return to the place where he had clarity: home. Here, he sees a version of himself out in the schoolyard and gets some great advice. "Take a look at your family assets and make a new list, of everything you thought was progress - that was bullshit. I know your life is full of turmoils and spoiled by fantasies of who you are, I feel bad for you." The realization manifests into a jazzy explosion of questions. Kendrick takes every instance of his life in which he thought he found himself and brings them all into question. If not in money trees or swimming pools or Wesley's theory or the new walls then where? For now, probably the backseat, right where he started.

On "Hood Politics", Kendrick's trip home gives him the burst of energy and confidence he needs. Kendrick adopts his old moniker (K-Dot) for a firebrand return to day one to remind himself of everything he knows to be true. He revisits Compton memories, throws shade on the enemies, and repossesses his own mentality on the industry and the government. "Everybody wanna talk about who this and who that? Who the realest and who wack? Who white and who black? Critics wanna mention that they miss when hip-hop was rappin. Motherfuck you, if you did, then Killer Mike would be platinum." The realigned sense of focus is swiftly followed by Kendrick's biggest lesson yet, a grocery store meet-up with God in the form of a begging drunk. Refusing to give him money because of how he appears, Kendrick chooses to walk on by until the man announces his real identity. It's here that Kendrick takes all the misused influence, all the resentment, all the desire to fend off the critiques of his power, and decides to give it away. "How Much A Dollar Cost?" he asks. Well, in Kendrick's context, there are a lot of follow ups. Who is giving it to you and for what reason? Who are you giving it to and what do you want in return? In the light of a drunk with a semi-tan complexion, Kendrick realizes it's not his place to judge on any grounds. He just needs to offer what he has. If that's money, it will be money. If it's love, it's going to be love. But when it's power - when it's the influence that he's been learning so painfully how to use with intention over the course of To Pimp A Butterfly - he's going to use it to make the world a better place, with a little help from his heroes.

While Kendrick talks to Tupac throughout the record in the form of his ongoing self discovery, he really begins to jump into his footsteps on "Complexion". Not altogether unlike Pac's "Keep Ya Head Up", here, Kendrick gives the truth as it stands, unfettered by all of the subtext, all of the overarching institutional white noise, all the idiotic image projection keeping every human being from healthy self-love. Here, Kendrick talks about race in America in 2015, and he does it in a way that should be heard in as many speakers across the country as possible (thank you Spotify).

With the help of an incredible guest verse from Rapsody, this track redirects the focus from the bright lights and the "Call your brothers magnificent, call all your sisters queens", Rapsody sings, "we all on the same team, blues and pirus, no, colors ain't a thing". With Pete Rock on the scratches and Thundercat on the production, there is very little keeping this track from being one of the best on the record. It's a final moment of refocus and restrengthening before going back up to the top from here on.

"The Blacker The Berry" sees Kendrick take "Keep Ya Head Up" straight on, though the context has shifted tremendously from the original. Here, Kendrick echoes many of the same thoughts that Tupac gave us 20 years ago - ones that still have yet to be addressed or corrected in any form by the institution that perpetually chooses segregation and line-drawing as its primary mechanism. "They may call me crazy, they may say I suffer from schizophrenia or something but homey, you made me", Kendrick sings. Whatever it takes, right? If it's conscious Kendrick singing "I love myself" over a "crossover" hit track, welcome him with open arms. But if it's "I love myself" Kendrick heralding his blackness and his roots in the same sentence, call Kendrick crazy. It's a formula we've seen before - one that in 2015 happens at an inexcusable rate. And that's what brings us to Kendrick's devastating last line: "So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street? When gang-banging made me kill a nigga blacker than me - hypocrite." Kendrick personalizes the weight we all need to realize we hold: by accepting the institution as it currently exists, drawing lines where convenient for the dominant majority, we are all guilty by accessory - hypocrite.

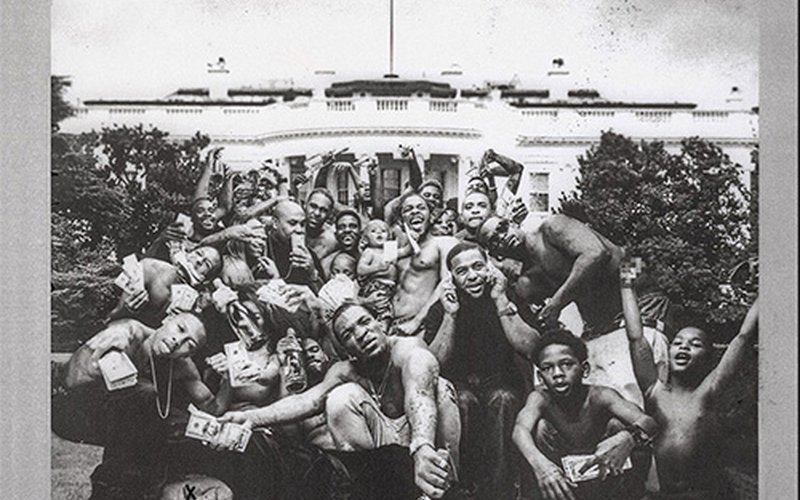

After reminding us to be true to ourselves on "You Ain't Gotta Lie", Kendrick brings us to To Pimp A Butterfly's first single: "i". We've all heard this track a thousand times at this point. The track won two Grammys, it's been viewed 17 million times on Youtube and it's been the most puzzling move of Kendrick's career until now. Here on the record, we have a live version of the song, complete with Kendrick being introduced as "the biggest rapper in the world", taking a break from lyrics to pump up the crowd, then eventually breaking it off three-quarters of the way through to talk to a crowd who seriously misunderstands the point of the song at hand. "i" is more of a prayer than a proclamation - it's Kendrick trying to remind himself that the institution's constant whispering need be silenced for a moment of remembrance. As Kendrick gives us the translation of the Ethiopian word "negus", you can hear the crowds silence to a standstill, and the video for "i" comes back into focus. In this new context, the video looks less like Kendrick leading a parade down the street and more like going up and out of Compton like he did the first time. But here and now, he's learned his lesson, and he's not trying to pimp the butterfly like he did before. This time, he's taking all of Compton with him, right to your doorstep, and he doesn't need to explain himself. There he is on the cover, on the steps of the White House with a small army around him. He may not be front and center, but he sure has the biggest smile.

Kendrick ends his album with a last lesson. It's the one that he needs his hero for the most. The lesson is this: Kendrick is not perfect, neither is he immortal. With a spectacle of idols ahead of him, in the grave but still looking down at Kendrick from the stars, Kendrick ponders over the earthly fate of so many of those: being known for your missteps rather than your successes. It's this fear that Kendrick still grapples with. He wants to make a difference, and with what To Pimp A Butterfly shows, he's done his damnedest to that end. But he knows there is a ceiling. He can strive for change, but if worse comes to worst, will it make any difference? On good kid, m.A.A.d city, Kendrick had a dream. On To Pimp A Butterfly, he lived the full Icarus story of coming to make it a reality. And now, he can only hope that with time, his words, his stories, and the power he chooses to give away makes for a better tomorrow, because God knows the institution doesn't take kindly to disturbances. Kendrick's talk with Pac ends abruptly, a pop and a silence, not unlike the gunshot that rang out in September of 1996 that ended his life. But where Pac left his legacy, Kendrick continues it - not directly behind, but rather, alongside. Kendrick Lamar has had his day pimping the butterfly, but after reaching the top of the industry, he realizes that even his newly realized strive for love and understanding can be part of a larger racket - there's always another opportunity to take your influence and make money off of someone else's problem. But to echo once more, "shit don't change until you get up and wash your ass". Kendrick is done washing - now it's our turn.

As you already are fully aware of, To Pimp A Butterly is out now. Grab it on CD at your local record store - no vinyl release yet. Kendrick's first live show with the new material in his repertoire comes this Memorial Day weekend at Sasquatch! Music Festival. If you haven't bought tickets yet, you now have more reason than ever. Grab tickets here.

Hunter Hunt-Hendrix cannot catch a break. With his work as Liturgy, he has crafted some of the most vivacious, jarring metal records we've heard in recent years. Take 2011's Aesthetica as an example. The record operates between quiet and loud like little else on the market. Its use of black metal t…

Regardless of whether you consider the new release by Courtney Barnett her sophomore effort or first official LP, there's no denying it's a terrific album. In fact, if you were a fan of last year's Double EP: A Sea of Split Peas, I'm happy to tell you that Sometimes I Sit and Think, and Sometimes I…