In the dimness of the cabin lights, I strain to read a comic book on a flight from New York back to Seattle. Suddenly, the overhead light beams down, illuminating the pages. I look toward the window seat and see it was the older gentleman next to me who turned it on.

“You have to protect your eyesight,” he says, smiling. “Before you get to be my age.”

We’d been on the flight for an hour or so and hadn’t said a word to each other. He’d been sitting quietly the whole time staring out the window while my wife, Kristin, slept to my right. With this exchange, we begin to strike up a conversation that unexpectedly continues for the remaining hours until we reach our destination. He introduces himself as Joven.

We exchange pleasantries for a while, telling me he’s a doctor and that he’s off to visit his grandchildren in the Pacific Northwest. At some point, he mentions that he’s Filipino and I casually mention that my wife is as well. Suddenly the conversation livens up. She awakens right on time as Joven pulls her into the conversation, eagerly asking questions. “You’re from Ilocos? My wife’s family’s from Ilocos!”

He finds out about my job at KEXP and that my wife is a musician herself, which only excites him more, overjoyed to hear that we’re pursuing work in the arts and confides that often he wished he’d taken that path. Slowly he begins to tell us his own story. How he immigrated to New York City from the Philippines in the 1970s. The excitement of being in the city, the prejudices he faced. But mostly, he wants to talk about the music of the city he fell in love with. Specifically, the opera.

He regaled us with stories of sitting in the park with his lunch, taking in the free opera performances the city would host. Venturing out to staged performances, witnessing some of the greatest productions in the world. Through this, he begins to tell us about Evelyn Mandac – an esteemed soprano and the first Filipino to ever sing at the world-renowned Metropolitan Opera House.

Ms. Mandac was not easy to find. After we’d gotten home, my wife showed me some recordings of Mandac and we were both blown away. Months after our encounter with Joven and in the early stages of the COVID-19 quarantine, I began to try and find Ms. Mandac. Reaching out to the Metropolitan Opera, Filipino opera organizations, and varied email addresses scraped from the depths of the internet provided no leads. Then earlier this year, I was reading through the comments on a YouTube video with her performance of “Lascia ch'io pianga” George Frideric Handel’s Rinaldo when I saw a note: “Ms. Mandac is very happy to hear this recording is on YouTube. She sends her heartfelt gratitude.”

As a hail Mary, I replied with my contact information and asked if the anonymous commenter could connect me with Ms. Mandac. Weeks later, I received a reply with Ms. Mandac copied, accepting my proposal for an interview.

She’d ask that I call her to schedule a time for our formal conversation. When she picked up the phone, not only was I in awe that I’d finally reached her, but the camaraderie between us was instant, if not serendipitous. I confided that I was most definitely not an expert in opera, to which she asked how I’d found out about her. I told her it was from a man on a flight.

“What was his name?” she asked.

“Joven,” I replied.

“Joven!” she exclaimed.

After cross-checking with a few of the details I recalled about him, she began to laugh. Joven was a friend and with connections to her own family. We both were astounded by the likelihood of a mutual acquaintance and the smallness of the world. I told her bits about my conversation with Joven and the connections we made with my wife. She gasped again when I told her my wife and her family were from Ilocos, saying it’s where her father was from. She even knew their hometown of Bangar, a small town in La Union province that she’d passed on her way to Laoag.

Our initial exchange was more than I expected as she questioned me about my own travels to the Philippines and my favorite Filipino foods. Never would I imagine that I’d be discussing the deliciousness of pancit and adobo with a bona fide opera legend. We both marvel at the smallness of the world and these surprising connections. But, as I would learn, Mandac's life has been full of surprising moments like these.

“It's so, so interesting, Dusty, what happened to my life,” Mandac tells me. “You know, they talk about luck or something. Being there at the right time? Well, it seems to have happened in the early part of my life.”

Evelyn Mandac was born in the City of Malaybalay in the Mindanao region of the Philippines in 1940. She describes her father as having a beautiful baritone voice and once having his own ambitions to sing, but her grandfather urged against it, telling his son, “You’re not going to earn money. How are you going to support your family?” So her father pursued a degree at the University of the Philippines, becoming an engineer, enlisting in the army corps, before being stationed in Mindanao. After the end of World War II, the family moved to Manila – Mandaluyong specifically – and lived on Shaw Boulevard.

“Everybody made fun of us whenever I gave my address of Mandaluyong because there was a mental hospital close by,” Mandac laughs. “And so they always kidded me about it.”

Growing up, Mandac’s parents sang in the church choir. Once she was old enough, Mandac joined the choir as well. But it was studying at the University of the Philippines where she began to hone in her vocal prowess, moving from the chorus and receiving instruction from Lourdes Corrales Razon – a gifted mezzo-soprano and famous Filipino radio personality in the 1940s (Razon’s grandson Martin Nievera continues the family’s gift of voice as a celebrity singer and television host in the Philippines). Mandac credits Razon for helping her develop the foundation of her vocal technique and remembers her as “a very loving and generously caring teacher.”

Before her death, Razon told Mandac to seek out Aurelio Estanislao. Estanislao was a renowned baritone singer and steadfast advocate for Filipino vocal music. His resume was stacked with awards, including recognition as the first Filipino to win a Premier Prix du Chant from the Conservatoire Nationale du Musique de Paris, among other international vocal competitions.

“[Estanislao was] a very brilliant man. He took great interest in me when I became his pupil,” Mandac recalls. “He taught me so many things about the ‘art song,’ which is ‘lieder’ as they would say in German or the ‘kundiman’ as they would say in the Philippines. Songs that are based with poem and the music given by the composers during the early times.”

This study of art song and kundiman – the genre of traditional Filipino love songs – with their lyrical, poetic approach captivated Mandac. She says she “fell in love with that world,” Estanislao guiding her through art song in French, Italian, German, and Spanish. These ideas in some ways were precursors to Mandac’s destined pursuit of opera. This fate was fast approaching as Mandac honed in on her talent and found herself being invited to sing at more and more events. Destiny arrived when she performed at a big soiree for U.S. Ambassador and cultural attache William Stevenson.

“[Stevenson] came to this soiree and I sang, of course. And after he spoke to me and was very interested in what my plans are and everything.” Mandac says. “And he said, ‘I can get you a scholarship at Oberlin College.’”

As it would happen, Stevenson had served as the president of Oberlin College prior to his diplomatic work. Suddenly, Mandac had the opportunity to study at one of the most prestigious music conservatories in the world. However, this did not include a travel scholarship and the costs were too tremendous for her father’s army salary. So, Mandac applied for a Fulbright scholarship and got accepted.

In February of 1964, Mandac packed her bags and left the warmth and comfort of the Philippines for Oberlin, Ohio.

“It was winter at that time and it was fascinating coming from a warm weather country to come to winter immediately,” Mandac says, adding with a laugh, “It was quite a big change, but I was so fascinated with snow. “

Mandac was picked up at the Cleveland airport by her uncle, Dr. Vallejo (Mandac jokes that he’s not actually a relative, but points to the Filipino tradition of calling your parents' close friends aunts and uncles). She would stay with Vallejo and his family for two days, the first 24 hours of which she slept.

“I was exhausted, I’d never traveled that long in my life,” Mandac says.

Despite the rapid change in her environment, Mandac says she loved her first semester at Oberlin, even the winter weather, joking that this was “very strange for a person who lived all that time in the Philippines.” Though it was her first semester there, the college was already into its second semester of the year. This wound up working tremendously to Mandac’s advantage.

“A lot of the star singers went to Mozarteum in Salzburg to have their third year of college experience. And so low and behold, I sang for the conductor there who was in the residence, and he used me a lot in the concerts that they have when they needed a soprano singer,” Mandac says.

Following the disastrous earthquake in Anchorage, Alaska in March of that same year, Mandac was invited by Oberlin’s conductor Robert Fountain to journey up Northwest and perform a recital. She describes it as a professional experience and a rare opportunity that she would likely not have had given her recent admission to the program. But the combination of the other students being away and the power of her voice had opened a door.

Fountain took to Mandac and continued to invite her to perform when opportunities arose. She also became close with Oberlin voice teacher Daniel Harris, who went out of his way to not just instruct Mandac but make her more comfortable in her new setting. A religious man, Harris often invited her to church with his family on Sundays and have her come to their house for lunch.

“They looked after me. I'd never experienced being away, so, I was so homesick at that time. But they took care of me. People always took care of me. And that's why I felt so fortunate, you know? And it made me appreciate friendships, people,” Mandac says.

Mandac did encounter misconceptions about the Philippines from her teachers and others in the United States. She often found people thought her home to be more “island-like,” unaware of how industrious Manila and many of its major cities actually were at the time. Despite the inaccurate understanding of her home, Mandac says these misunderstandings amused her.

“My teacher was not really familiar with the Philippines, so he thought we were island people. Sometimes he was thinking, 'were you living in tree tops?' Or something like that,” Mandac laughs. “I mean, at that time, it was really strange to hear that. But he was so innocent about it and he thought we were still a colony of the United States.”

As her time at the Oberlin Conservatory came to a close, she applied to Indiana University and to The Juilliard School in New York. She was accepted into both.

“I mean, Juilliard was the cream of all the conservatories. So I thought I’d go there. And so I went,” Mandac says.

As a part of her admission to Juilliard, Mandac had to audition in front of judges comprised of faculty before she would be accepted.

“After I sang, they said, ‘Did you have your education in Europe?’ I started laughing. No, I said, I studied in the Philippines. And they were very surprised that my schooling was, I guess, very good,” Mandac remembers. “They accepted me immediately and gave me a scholarship.”

In conjunction with acceptance, Mandac was awarded the Rockefeller Scholarship to pursue her Juilliard studies. However, a stipulation for the scholarship was that for one year abroad in the United States, she would need to go back to the Philippines for two years. Her former teacher, Estanislao, who faced similar stipulations early in his career, urged her to stay in United States and not come home. With her career trajectory only moving ahead, Mandac worried about stalling her opportunities.

“I went to the Rockefeller Foundation and I said, what can I do?, Mandac says, “[They said] 'Well, we've been following your career. I think there's always an exception to the rule.' So I was let off. That's why I feel so humble that I have to give back a lot.”

Mandac lived in the International House across from campus which comprised, she surmises, of about 60 percent Americans and 40 percent foreigners. She recalls only one other Filipino at Juilliard, but quips that the person “wasn’t competition” because she was a mezzo while Mandac was a soprano. Asked if the program was competitive, Mandac exclaims “Oh my goodness, yes!” which leads her to what she considers first “failure.”

In her second semester at Juilliard, Mandac became fascinated by the opera. Juilliard voice teacher Hans Heinz was instrumental in fostering this newfound love, opening up Mandac to the world of opera that she hadn't yet explored. She auditioned for the Juilliard opera program and wasn’t admitted.

“I felt that’s the end of my musical world, you know, I just felt so unhappy about it,” Mandac says.

Christopher West, director of the Juilliard Opera Theater, consoled Mandac and told her she could audition again the next year.

“So I did. And I got in, “ Mandac says. “And from then on, I sang the main roles for the opera.”

Mandac’s admittance into the Juilliard Opera Theater spurred a bond between herself and West, who’d taken a fondness for the burgeoning opera singer. West's favorite soprano he’d previously been working with had graduated, and there was Mandac, once again in the right place at the right time.

West came to Juilliard from Royal Opera House in London’s Covent Garden where he’d been serving as the resident stage manager. With a prestigious mentor, Mandac began to finetune her skills as an opera singer.

“I learned everything from him. How to act and how to move. I mean, all of these things were great lessons for me. It was like it was my foundation of what was going to happen to me,” she says.

Mandac would sing the soprano roles in several of West’s productions at Juilliard, including Mozart’s ‘The Magic Flute’ and Giacomo Puccini’s ‘La Boheme.’ West was particularly impressed with Mandac during their run of Mozart’s ‘Marriage of Figaro.’ Mandac played the role of Susanna, one of the longest roles for a soprano that rarely has the actress leave the stage. After a successful opening night, Mandac was ready for a day of rest when West called to let her know the other soprano was sick and she would need to perform the role again that night. He told her to put her feet up and rest. Mandac says it was a lesson in always needing to be prepared for these surprises. She would end up performing the role three nights in a row.

West was grateful to Mandac and began giving her more roles. The gratitude was mutual. Under his direction she’d learn four operas of the standard repertoire, setting her up for future successes in her career. She’d also become something of a muse in his program selection.

“Sometimes these directors, when they like you, they think of the opera that they’d like to do [so] you can be one of the main roles,” Mandac says. West would even use her for the American premiere of Richard Rodney Bennet’s ‘Mines of Sulphur.’ Tragically, however, during this production West died from cancer, leaving Mandac devastated but with deep gratitude and respect for her director.

Following her time at Juilliard, Mandac would make her professional debut in 1968 in Mobile, Alabama performing Carl Orff’s iconic Carmina Burana. It was not the last time she would perform this soprano part either – her voice would be immortalized in a 1969 recording of the piece with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and legendary Japanese conductor Seiji Ozawa, an icon of opera in his own right and infamous for conducting in a white turtleneck instead of formal dress attire.

Asked if she was nervous ahead of this debut performance, Mandac quickly replies, “Oh absolutely. I’m always nervous.” But she likens the nervousness to that of a professional athlete – having the confidence that she can perform, but an eagerness in the anticipation to get out there and sing.

“The whole day [before a performance] is a very quiet day for me. I don't want to see anybody. I don't want to talk to anybody, including my husband. I would send him out or something like that. I don't want any disturbances. I'm very monastic about that,” she says.

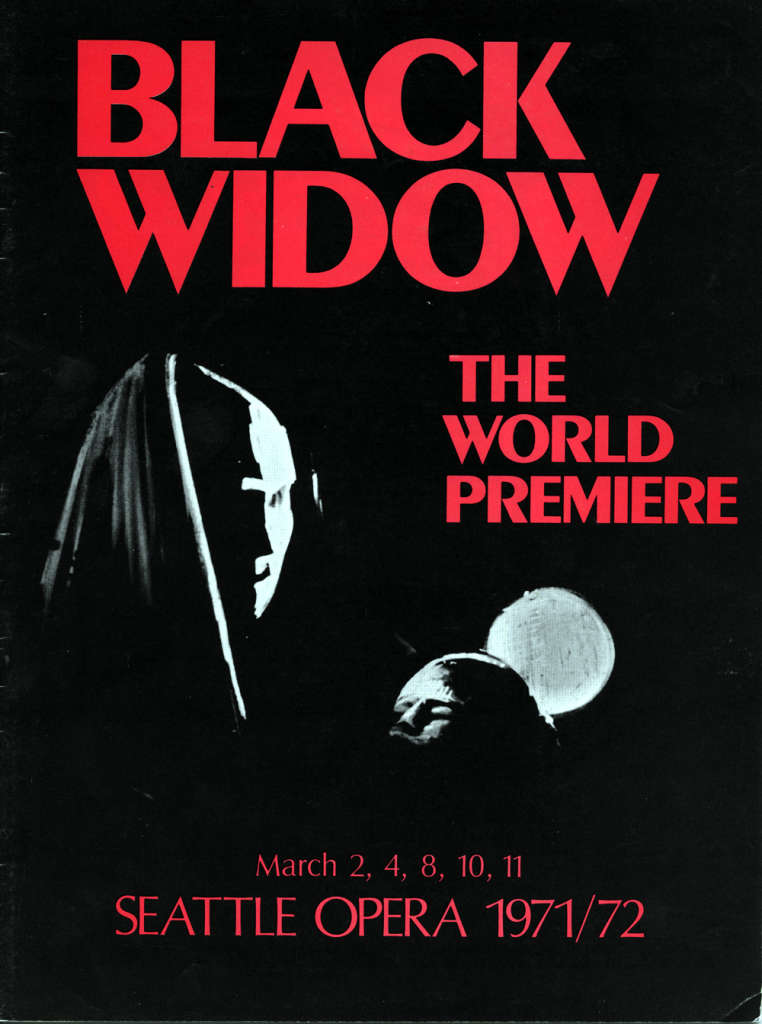

Her career swiftly taking off, Mandac soon found herself traveling across the country, including invitations to perform with the Seattle Opera.Her first performance in Seattle was in 'Turandot,' performing alongside the legendary Swedish soprano Birgit Nilsson. This astounding opportunity cemented her relationship with the Seattle Opera, returning for such productions as ‘Carmen’ and ‘La Boheme.’ Perhaps most notably was the world premiere of ‘Black Widow’ composed by her Juilliard colleague Thomas Pasatieri. Mandac says Pasatieri was a fan of her singing and was thinking of her voice as he composed the work.

“He knew my voice, so everything to me seemed so easy to do. Of course, you work hard, but it was just made for my voice and I'm ever so grateful to him,” she says. “It reminds me of those early days of the early composers. They had the people in mind. They had the singers in mind when they did some compositions. I think, you know, their favorite singers and they use them a lot.”

‘Black Widow’ wasn’t even the only Pasatieri opera she’d inspired, citing his commission for the Baltimore opera ‘Ines de Castro’ as another work inspired by her voice. In 1972 she would also sing in the American premiere of Italian composers Luciano Berio’s ‘Passaggio.’ Berio would later invite Mandac to perform the role again in Italy.

In 1971, Mandac would make her television debut in a rare and ambitious adaptation of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s ‘The Queen of Spades.’ The performance debuted on PBS and found Mandac playing the role of Lisa, the love interest of a young officer, opposite of opera titan Jennie Tourel (the two would also work together on ‘Black Widow’ in Seattle that same year). Tourel was also still teaching at Juilliard and would occasionally invite Mandac to sing at her masterclasses.

Throughout the next few years, Mandac continued on a remarkable trajectory. She performed in ‘L'Africaine’ at the San Francisco Opera alongside stars Placido Domingo and Shirley Verrett, star in Handel’s ‘Rinaldo’, and numerous others. Then in 1975, Mandac made her formal debut at New York’s Metropolitan Opera performing as Lauretta in ‘Gianni Schicchi.’

Asked what the experience was like to first step on The Met stage, Mandac says it was, “scary, but you have to do it for the love of it and for a chance to sing in such a great hall.” She is quick to point out though that she has the distinction of having sang on both houses of The Met. Previously in 1966, she won the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions, getting the opportunity to sing at the old Met opera house before it was demolished in 1967.

“Oh my God, that stage with all the heavy velvet curtains,” she remembers. “You could see the dust come off when it moved. It was that old and ancient, but it had great traditions. All the great singers, early great singers sang there. I felt so humbled by the chance to even sing there, just even just for the Met auditions.”

At the new Met, performing in a full production, Mandac became the first Filipino to grace the stage. Newspapers and magazines like Billboard noted this fact and it’s something Mandac says she was aware of.

“It was a big, humbling experience and I guess an honor because you can't help... I mean, people always think that you represent the country, but that was very far in my mind at all,” Mandac says. “I mean, my idea was to sing and I'm just very fortunate and such gratitude, that's how I felt.”

Recordings of Mandac’s performances from the Met are difficult to find, but this brief selection of “O mio babbino caro” captures a transcendent moment for Mandac. Her vocals, effortlessly soaring above the sweeping orchestral swells. Mandac would sing several performances of ‘Gianni Schicchi’ as well as one performance as Gretel in ‘Hansel and Gretel.’

In the late 1980s, Mandac decided to retire from performing.

“I just felt it's time for me to go into another place,” Mandac says.

Around this time, Mandac had begun teaching voice and was finding great joy in this new work. It was a love fostered by a fellow teacher, Judith Natalucci. The two met through Mandac's husband who'd discovered his secretary was taking vocal lessons. Curious, he asked to meet Natalucci and was impressed enough to connect the instructor with Mandac. Mandac considers Natalucci crucial in her own development as a teacher, teaching techniques in a way that aligned with how Mandac was already practicing as a vocalist. The two remain good friends to this day. It encouraged Mandac to move on from performance and pursue teaching full-time. After years of being gone six months out of the year and way from her husband, it felt like the right time.

“I don’t miss the stage,” she says. “I loved it when I was there. And I think that I love teaching right now.”

Mandac continues to operate a voice studio in New York – adopting a virtual model with the COVID-19 pandemic. As time goes on, she’s watched her students embark on journeys similar to her own. Traveling and performing internationally, singing on the grand opera stages. Some of them have now become teachers themselves, occasionally inviting Mandac to guest at their masterclasses or even reaching out for more lessons from Mandac to continue honing their crafts.

“I feel like I'm a student forever,” Mandac says. “Even now, as a teacher now, I'm still learning. And that's the kind of habit that you develop. And I believed in it. Work is learning. Open to new things, open to old things, and then just integrating them all together. That's how I feel about life.”

For a while, Mandac would also return to the University of the Philippines to teach master classes. She recalls a particular instance when she arrived and found the students ill-prepared

“I said to them, 'This should not happen. You have to be prepared when you work with somebody who is going to coach you. How can we work when you don't know what you're doing or you're singing, you don't know what you're singing?” she says.

The next time she returned to visit family in Cagayan de Oro, she came back to visit the students for another master class and found that the students had taken her feedback to heart, showing up completely prepared and performed a concert with her demonstrating everything that they’d learned.

“I was just in tears,” she says. “They were singing from their hearts. It was so... I mean, I was so touched that they took my big scolding to heart.”

For Mandac, it was embolic of a central philosophy that has served her well – always be prepared.

“They say that [to have] a career you have to be lucky, which is true. But luck is not enough. You have to be prepared when the door opens, you have to be prepared. There's a thing when the door opens, don't let your pants down. Don't be caught with your pants down.”

As time has gone on she's lost connections she once had with the University, and the pandemic has made visiting the Philippines nearly impossible. Something she regrets and hopes will change soon. She pines for more opportunities to go home and pass along her wisdom.

“I wish I had more opportunities to go home. I hope so. It will change. I'm not sure with the pandemic, of course, there's no way,” she says. “Because you know what? Filipinos have beautiful voices. We have a pool of up-and-coming artists that are so eager to learn and I have much, I must say, to share.”

Though restrictions have kept so many apart, over Christmas in 2020, Mandac volunteered her time to music direct a virtual production of Handel’s ‘Messiah,’ bringing together vocalists and musicians from across the globe for a livestreamed performance. A tactical and timezone challenge, but one with the worthy cause of raising funds for out of work Filipinos in order to support their families.

Nearing the end of our call, Mandac continues to tell me stories. We jump around throughout the discussion from her times in school, silly moments of improvisation on stage that actually worked, and the thrill of premiering new works. And as she mentions some of her collaborators, she notes how so many of them are gone now.

“You know, it's interesting about life,” she tells me. “You lose all the people that you have connected. And now you meet new people to connect with. So it's never-ending. It continues, the learning and the giving. This is just what life is all about. And the love for what you do.”

Reflecting on this, I start to think back again to my conversation on the plane with Joven. I recall the point in which our talk began to wind down as we approached Sea-Tac airport from the sky, sitting in silence. Outside the window, we’re gifted with one of the Northwest’s trademark beautiful sunsets. Orange and purple hues lighting up the sky, silhouetted by evergreen trees. Joven musing about a life well-lived, a bittersweet notion with an implied sense of reaching the end of a story. Something akin to a cadenza, the last pause and flourish before the music reaches its finale.

I think back on the serendipity of these two conversations. A butterfly effect of one kind stranger opening himself up his life story, leading to myself hearing Mandac’s from her as well. There’s a temptation to ascribe meaning to it all. Certainly, there’s the smallness of the world we live in, an interconnectedness between us all hidden in plain view. But it’s also the sharing of stories and knowledge itself that strikes me now. Aurelio Estanislao, Lourdes Corrales Razon, Christopher West, Evelyn Mandac, Joven, and so many others sharing what they know with others and how that knowledge spans generations – and likely generations prior even.

Ms. Mandac perhaps put it best when she calls herself a forever student. Her life is an example of embracing the moment, doing the hard work, and pushing your own boundaries along the way.

Martin Douglas examines one of the most beloved artifacts from Detroit's much ballyhooed early-'00s garage-rock scene.

In honor of Pushing Boundaries, and in celebration of the album's 25th anniversary, KEXP's Janice Headley revisits Cibo Matto's genre-defying 1996 debut full-length Viva! La Woman.

We caught up with Icasiano to dig into his love of improvisational jazz, his first ancestral trip to the Philippines, and how his love of Filipino food continues to connect him with Filipino culture