In honor of Funky Drummer Day, local musician and journalist Trent Moorman has graciously shared interviews he's done for The Stranger and Vice Magazine for 24 Drummers, 24 Interviews, a four-part series here on the KEXP Blog!

Tune in tomorrow, Wednesday, March 9th from 6:00 AM to 6:00 PM, for Funky Drummer Day itself! KEXP DJs John Richards, Cheryl Waters, and Kevin Cole will pay tribute to one of the most sampled breaks in music history: the iconic eight-bar unaccompanied solo by session drummer Clyde Stubblefield in the 1970 James Brown single “Funky Drummer.”

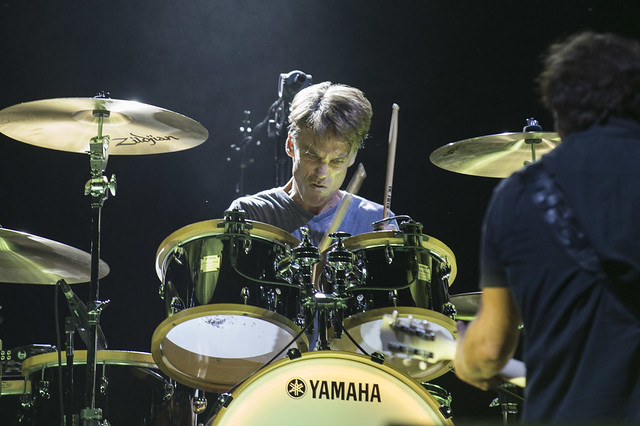

[ all photos, unless otherwise credited, courtesy of Trent Moorman ]

Frankie “Kash” Waddy (Funkadelic/James Brown)

How did you start drumming for James Brown?

We were studio musicians in Cincinnati at King Recording Studio. We were still in high school and would tour with different acts on James's roster. James was having trouble with his band and was making a switch. So he flew Bobby Byrd to Cincinnati in a Learjet to get us. The night before, we played a place called the Wine Bar for $15 total. The next day, Bobby Byrd put us in a limousine and shot us to the airport. We never even went in the direction of the airport, it wasn't in our vernacular—we didn't fly. [But] we flew to Columbus, Georgia, and they took us to this big venue. It was the National Guard Armory. We went in the back door. On the left side was the dressing room with all the cats we idolized—Fred Wesley, Maceo Parker, Kush Griffith. On the right-hand side, it was James's dressing room. It all happened quick. We had just flown and been in a limo for the first time. They shoved us to the stage, and it's the biggest crowd we'd ever seen. We gathered in a little huddle to play because we were used to being on such small stages. James came onstage, counted off a song, and that was that.After the show, James screamed, "Y'all did great! Y'all killed me!! I'm going to give you $225." And we were happy with that. Then he said, "Naw, I'm gonna give you $250." And we thought, "Wow, a raise that quick!" Anyway, he did this counting all the way up to $450. The whole time, we were writing the amount on paper. Finally, James said, "What is that y'all are writing down?" We had to write it down so we knew how much to divide up between us. James laughed out, "Naw! You ain't splittin' nothing. That's for each of you!" Good money.

We had an old Dodge station wagon. We went from that to a Golden Eagle bus and a truck stocked full of brand-new Vox equipment. James and the Beatles were the only ones that had Vox endorsements. We had three changes of uniform, matching shoes... it was a trip. We were pinching ourselves like crazy because we couldn't believe it.

Can you talk about playing with bassist Bootsy Collins?

He and I have a thing that's so special. We're brothers. We've been through everything together. We went through James Brown, then to George Clinton's Funkadelic together. We've always made sure that he, his brother Catfish, and myself stayed together. When Bootsy and I play together, it's a no-brainer. It just works.

What makes you and Bootsy such a good rhythm section?

One of the major factors is the one. How we gravitate and generate, and accelerate from the one, and back to the one. And we just know each other so well. We've done everything together our whole career. We always had a small group. We didn't have a lot of money, and we couldn't afford a lot of people, so we had to play really tight. Everything had to be compound, and big. We talk from time to time about it, and we actually try not to figure it out. That way we won't mess with it. It just is.

Of the James Brown songs you've been a part of, which is your favorite?

It would have to be "The Grunt." One of only two instrumentals recorded by the original J.B.'s lineup with Bootsy and Catfish Collins. That one is so important to me because my father had had a talk with James about his intentions with us. And James said, "You know what? I'm gonna give them that song. I'm gonna let them have it." And he did. He made that song ours. He gave us all the rights and publishing on it. I'm still getting royalties on it to this day. James was a man of his word. He did what he told my father he was going to do.

James was made of music.

Yes. And we stayed with him as long as we could. He was older. We were real young and wild. We learned the world from him. Something not a lot of people know is that while we were with James, Jimi Hendrix was wanting us to be his band. He wanted a more black act, after being with [Noel] Redding and those guys. Jimi needed us to quit James, though, and he was going to pick us up. I was game, but the other guys didn't feel good about having to quit James.

It all worked out. We ended up then being in Funkadelic, which was a real free musical situation. With James it was a more strict, militaristic, disciplined type thing. With George Clinton, he was like, "Do whatever you want to do. Don't ask me nothing. If you can think it, you can do it." We went from one extreme to the other. We brought that professional discipline to Funkadelic. And it's still working. I'm still with P-Funk. And I'm still with Bootsy's Rubber Band. I'm the link between both groups.

What's your favorite Funkadelic song you've been on?

I'd say "Bop Gun." There are a lot of live recordings of that one that came out. That song had significance. I think it still stands up.

What was a Funkadelic session like?

George ran it like a factory. There would be two or three rooms going, and whoever got in there first would start putting their stuff down. Whoever wanted to join in did. Some of them came out really, really good. And some were just okay. But the great ones were worth it. Funkadelic recording was like an assembly line. One group of guys would record, then there'd be another group of guys waiting in the next room to lay down their thing on top of it. We went on like that forever. And while we were in the studio, we wouldn't listen to the radio or watch TV. We didn't want to be distracted or infected by anything. We didn't want to sound like something that was already out there.

Matt Cameron (Pearl Jam, Soundgarden)

How can drummers put themselves in a position to make money from their drumming?

Money was never the goal for me, being good was the goal. It's more difficult now than it was when I began. Being able to program with music software is crucial, and it always helps to know how to read a chart. In music, there are good people and some bad ones, like any business. Focus on what you do best and believe in your abilities one thousand percent. No one wants a timid drummer.

What's your advice for new drummers?

What helped me early on was taking every gig I was offered. Playing different styles helped me find my own sense of groove. Practice with a metronome or drum machine. If you can't keep steady time, you won't get gigs. Most people in the audience don't notice good drumming, and that's okay. Your fellow musicians will. If the music is grooving and you feel inspired playing it, that's the ultimate reward. If you get a good reputation as a drummer and bandmate, you'll get gigs. Practicing alone is crucial, but you have to interact with other musicians to improve all aspects of musicianship. If it's recognition you're after, take singing lessons.

How do you go about licensing and publishing deals?

In the early Soundgarden days, we split our publishing equally. After a few albums, it wasn't good for band harmony to stay on this course. If the drummer doesn't contribute to the creative process, then they get no publishing [credits]. Once I started contributing as a songwriter, which took me years to do, not only did I receive a songwriter's share, but my role in the band became more valuable. I'm also fortunate to have worked with and learned from two of the best songwriters of my generation, Chris Cornell and Eddie Vedder.

Clive Deamer (Radiohead, Portishead)

How did you get involved with Radiohead when they decided they wanted a second drummer?

I think they recorded The King of Limbs and decided later how they would perform it. Which meant either using a machine or a second drummer to generate the polyrhythmic aspect. In one sense, I'm the machine.

Did Radiohead give you parameters for your drumming?

Not really. Philip and I quickly agreed it shouldn't become a macho double-drummer battle. There's enough of that rubbish on YouTube.

How is it playing with Radiohead? Is it like flying? It has to be like flying, right? Or free-falling, in an aerodynamic cathedral?

It's amazing playing with them, and fun. They let me do my thing. I do my utmost to make my contribution relevant. We get along very well on- and offstage. They even put up with my endless anecdotes about Robert Plant. [Laughs] As for flying, I'll leave that to your psychotherapist.

What would you say is the trickiest part of playing with a band like Radiohead?

Learning to say no to the cake trolley.

What has surprised you the most?

That after 38 years playing drums, people like you want to interview me. [Laughs]

Radiohead is one of the few bands on earth right now where the shows are truly experiences, dumb as that sounds. People are so into the music, and the music is so heightened, and lucid, and multi-leveled. It's a holy thing. What's that like? Does it ever get old? Are there ever moments where you're like, "Oh my God, Thom Yorke is Mozart"?

It's true that there is something very moving when a large body of people come together with such heartfelt love of music, and when the music is this good it's impossible to not be moved by all those happy-spirited faces. However, Thom's always shaking his ass around the stage, so I soon remember where I am. I doubt Mozart did that, and Thom doesn't read music, so does that answer your question?

Who was it that called Radiohead freak monkeys?

That would be members of The Westboro Baptist Church protesting outside the gig in Kansas City. Yes, they described Radiohead as "freak monkeys with mediocre tunes." Assuming the statement was aimed at me, too, I have no problem being called a freak monkey. I suspect I have the greater chance of evolving. I've also heard their music, and it's as sour as their negative outlook.

I like "freak monkey" as a description. What do you and the Radioheads listening to on tour?

On tour I've been listening to Santigold's Creator, Rye Rye and M.I.A.'s "Bang," Major Lazer's "Pon de Floor." I had fun in KC playing the chaps some of my fave R&B and jazz clips on YouTube: Les McCann and Eddie Harris's "Compared to What" live in 1969; Aretha Franklin's "Don't Play that Song (You Lied)" from the Cliff Richard show in 1970; Big Joe Turner with the Hampton Hawes All-Stars. Thom and I discovered our mutual love for Howlin' Wolf—a no brainier, obviously!

What do you think about while you're playing? Give me a snapshot of your drumming brain while at work. There's the magnitude and experience of all that is Radiohead—that sonic temple that the sound builds, that's put out there. Where the songs elongate and fold into worlds. What runs through your mind as one of the engines that's hammering down the nuts and bolts of the grand canopy? Do you ever think about the book you are reading? Or the glass of orange juice you had for breakfast? Have you ever read H. G. Wells's The Time Machine? I imagine that while you're playing, in the throes of the Radiohead elongation, your mind might wander to the subterranean world of Wells's Morlocks. Or to that glass of orange juice you had for breakfast. But while you're playing, the glass turns into the Mediterranean Sea, made of orange juice, and you're piloting an ancient Greek trireme warship there. Please tell me this happens.

The contents of my mind come out best through a drum kit, not the spoken or written word

Marky Ramone (The Ramones)

What’s your favorite Ramones song? If you had to say.

Okay, okay, let's see. I love "Rock 'n' Roll High School," but I also love "Sheena Is a Punk Rocker." I love "I Wanna Be Sedated." I love "Blitzkrieg Bop" [laughs]. It's too hard to just choose one. There are so many good ones, you know?

Of the Ramones albums you were involved in, which was the hardest to record?

We rehearsed a lot, so we were very quick in the studio. The album that took the longest was the one produced by Phil Spector: End of the Century. We usually made our albums in three to four weeks, but with Phil, it took five months. We weren't there that long; it was the mixing that took all the time. He put so many different instruments on that album that he had to keep listening to mixes and mixes and mixes. It wasn't rough making it, but there was just a lot of adventure going on in that studio, which I talk about it my book that I just finished. It'll be out in 2014.

So the whole Phil Spector holding you guys at gunpoint thing is a myth? But I want to believe.

Sorry, that was just some story. It's a good one. I would let it ride [laughs], but it's not true. I'm gonna be honest about it. I was in the studio the whole time with the other three Ramones. Phil didn't allow anybody else in the studio except for his engineer. He had a license to carry, but he never pointed them at us. Guns can get heavy, so he would take the guns off and put them on the recording console. I know he shot off guns with other people.

The Ramones hung out with Stephen King when you all did the song "Pet Sematary" for the movie based on his book?

Yeah, we got to hang out with him for a day and a night in Maine, where he lives. He was very happy we came to his place, and we were lucky we found it, coming all the way from New York. He was extremely hospitable. He brought us down to his basement that looked like a horror-movie set, and we sat around and ate dinner. He gave Dee Dee the book to read. Dee Dee took it home, read it, and then wrote the song in something like 40 minutes. He taught Johnny how to play the guitar on it. "Sheena Is a Punk Rocker" is also in the movie, in the scene with the baby and the truck—a crazy scene. Stephen would come to shows when we played in the area.

Is "Beat on the Brat" about a specific brat? Do you know?

Joey wrote that one. He was an unusual specimen, physically. As a kid, he got taunted and goofed on and teased a lot. After a while, that can get to you, like it did to him. So he wrote that song, "Beat on the brat, with a baseball bat." [Laughs] Of course, he would never have actually beat anyone with a baseball bat. Bullies are bad, because they always pick on the little guy—most of them are insecure, and they have to prove themselves. They'll never go up to the guy their size or bigger. My problem was I always fought with a guy bigger than me. And I never started a fight, it was always somebody hassling me.

I was glad when you and Joey made up on The Howard Stern Show.

The funny thing is, we laughed about that. We knew we had Howard going. When we went down in the elevator after the fight, we cracked up. And then we went back on to make up, because we knew he'd want us to make up on his show as a "part two." But really, it was good to make up, because Joey did die of cancer, and I was able to do the solo album he always wanted to do. Family squabbles are going to happen—we were like brothers. That stuff, you look back on and you laugh.

What studio did the Ramones like to record in? Was there one where you all seemed to click more?

We liked Media Sound on 57th Street in New York City. That's where we recorded. We liked the room—it was a big room, a lot of sound could bounce off the walls. Road to Ruin was recorded there, and out of that came "I Wanna Be Sedated."

On the production end, what would the Ramones aim toward for their particular sound?

We always made sure we had good production on the albums. A lot of punk bands would do it themselves, which I respect. And I don't mean this to be facetious, but a lot of their production wasn't good. Maybe they did that on purpose. I think the Ramones' production holds up today—we always made sure that we had good producers, because we knew in the end, it's the music that's the most important thing. And you want that music to live. We'd leave in dirt, yeah, we didn't want it too clean.

How does Marky Ramone want his drums to sound?

I want the drums to sound the way I tune them. I don't want effects on them. Just keep it nice and straight, and let the drum breathe. So that's what we did. The separation of the bass and the guitar always came out great. We'd record the drums first. Then bass and guitar. Then Joey would do his vocals.

Walk me back to Max's Kansas City. Sort of a hub for New York art and music for a bit?

Max's Kansas City was where all the New York punk luminaries hung out, and bands that would be passing through. People would talk, eat, and drink, and then from there we'd go to CBGB. On any given night, in the back room, you'd have the Ramones, David Bowie, Alice Cooper, Lou Reed, the Dolls, Johnny Thunders, Debbie Harry. You'd have Andy Warhol, Jayne County. The restaurant and bar were downstairs, and upstairs was where bands would play. Capacity was maybe 200 to 250 people. Very intimate. I just finished playing these huge festivals like Rock in Rio, so it's good to get back to venues with this current tour. Max's was smaller, a lot of people didn't have to play there, but they wanted to.

I spoke with Glenn Danzig, and he said punk is dead, and new bands calling themselves punk aren't punk. Do you agree?

Danzig was more into the horror stuff. I don't know if he's really a punk spokesman. I think there absolutely are good, new punk bands. I have a radio show on SiriusXM, and I hear a lot of great new punk stuff—Gallows out of London are really good, so are Riverboat Gamblers. I also like the Loved Ones. You gotta keep your ears open, you know? Lots of good bands are taking their cue from the Ramones, the Clash, and the Pistols. They mix it up and put their own spin on it.

Does it ever get old hearing bands that sound way too much like the Ramones?

I always feel like a band should be original. If they're that influenced by us, then great, I'm grateful. It's a compliment when I see a band in the jeans and the jackets, with Chuck Taylors, and counting off "One-two-three-four," and playing faster with songs that sound like us. I mean, that's been going on since 1977 when the Ramones went to England, and then England started its punk scene because the Ramones flipped 'em out over there. But in order to really be noticed, you can't sound exactly like your influences, because they're already there. You've gotta come up with something fresh—something that'll help you get noticed.

Mickey Hart (The Grateful Dead)

Mickey Hart is a theologian, a historian/archivist of planetary sounds. He's a big-bang worshiper, an author, and a Grammy-winning deep thinker. Life skims into and through his neurons as quantum physics and vibratory patterns.

I see you as a seer because of your abilities and experiences playing music, traveling the world, and collecting music. You've gone way in, and out, and looked into a different cauldron of life. You see and hear deeply into the world. What are your latest findings? What are the latest discoveries from Mr. Mickey Hart, Theologian?

I'll tell you. Speaking as Mickey Hart, Rhythmist, it's about the rhythm of things. Everything is interlocked. The world is rhythm. Everything in the world has a vibration. Anything that's alive and moves has a vibration. And if it has a vibration, it has a sound. And if it has a sound, there's an effect emotionally that it can have on you, spiritually perhaps. Whether it be through brain-wave function or something that makes you dance, it's all interconnected. Music is just a miniature for what's happening in the universe and deep space, from the beginning of time 13.7 billion years ago.

Hell yeah.

I'm trying to explain and allow people inside the vibratory universe. It's the key to everything. Life is rhythm, on simple terms. Like Einstein's theory of relativity: He wanted to boil it down to one little equation. Now I'm working in the cosmos, translating light waves into sound waves, from the big bang to the present. I'm looking at the science of music, as opposed to the art of music.

Light waves from space?

Yes. I'm working with NASA and scientists like George Smoot, who won the Nobel Prize in 2006 for his discovery of the big bang. We're changing radiation light waves into sound waves. Pulsars, galaxies, supernovas, black holes, stars, planets—they all have a vibration. And since space is a vacuum, there's no sound. The only way those vibrations can travel is through light waves. Once we've gathered those with radio telescopes, I take the algorithms and make sound out of it. And that's what this band I'm touring with now is about. The band will be playing these sounds and having a conversation with the universe.

What does it sound like? Whale song? Noise?

It's not noise when I get finished with it. It does come to me as noise. With computers, I make music out of it. It wouldn't be that interesting otherwise: It's very unharmonic, dense sound.

Like Slayer.

Not exactly. I open the light readings up and extract pieces from it, put it in various keys, and make music out of it. The band plays with it and has a conversation with the infinite universe. You'll be hearing sounds that no human has ever heard before. The sounds that spawned you. These vibrations that are your ancestors.

Whoa. Holy shit.

These are the seed sounds. This is where we came from. We came from vibrations, then we crawled out of the swamps with myosin proteins helping mobility, and became humans. But it all started with a vibratory origin. Music is controlled vibrations. This music comes from the beginning of time and space.

What is time and space? Why are we here? Are we even here?

Yeah, we're here [laughs]. There are many theories. Like the multiverse, where different times happen at the same time, different realities at the same time in parallel universes. String theorists say time moves backward and forward, and we live in all these dimensions simultaneously—that there are different realms of perception.

Like hallucinogenic drugs.

We're talking right now, but things are happening that we can't perceive. We are alive. And we do live in the past and the future simultaneously. Many levels of perception are available to us if we have the sensors to pick them up.

Do you believe in God?

If there is a god, it has to be a vibration. I don't believe in a god, I believe in a creational force. In my case, it's a rhythm—the beginning of time and space—the big bang, that's my god. Rhythm. There could be something that came before the big bang. Before the beginning of time and space. They say gases came together and caused an explosion, but no one really knows.

Right. So who made God?

God is a human invention. Humans try to explain the universe, which is unexplainable, so we come up with myths and legends, like God as a superior being that created all this. No one out there said, "Let this happen." It happened through a physical event 13.7 billion years ago. Even the Vatican recognizes that now. Organized religion is starting to come to grips with the God stories. Great minds have tried to explain the universe: Plato, Pythagoras, Kepler. Pythagoras gave numerical equations to the planets, the earth, the sun, and the stars. He saw the universe as giant heavenly clockwork. He discovered the octave, the fifth. A lot of the ancients were right, they just didn't have the instruments to measure it.

What do you think about the band Nickelback? That's not vibration. That's marketed, Walmart/Clear Channel schlop.

There are a lot of different sounds for a lot of different kinds of people. It's very much like food. Some people don't like asparagus. Some people can't eat meat. I wouldn't be presumptuous enough to comment on how good or bad Nickelback is or isn't. To some people, maybe it's the sound of God. Some people may think it's noise. And that's the way it should be. There's a lot of need in the world for sound. There are a lot of hardworking musicians out there trying to make good sound. If you don't like it, don't buy it. Then it will go away.

What are some of your findings on Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease?

When someone has a motor impairment, the neural pathways are broken somehow—from disease, a weakened immune system, the aging process, whatever. A lot of things can break the connections. Vibrations reconnect these broken pathways somewhat. We don't know how exactly, but we know that it does. That's the grail. It's like how finding dark matter would be to an astrophysicist or a string theorist—the glue that holds the universe together. Besides protons and neutrinos, 80 percent of the world is dark matter. We don't know what it is, but it's out there. It's the same thing with music. Music is very powerful. It's really only been used for celebration of life, dancing, entertainment, making love, and things like that. But now the therapeutic qualities in music are being noticed. Harnessing those, you have to understand where rhythm came from and where vibration came from. It's the big bang, of course, 13.7 billion years ago. The moment of creation, time, and space, and how it led us to being here, 13.7 billion years later, as Homo sapiens on this blue-green spinning rock. Once you know that, you can start to crack the code. There's like a musical DNA. How it works and how you can repeat it on a daily basis. Very much like a doctor would prescribe medicine. You can also think of music as medicine and prescribe music for certain ailments once we figure out the code. And that's what we're about to do.

The Grateful Dead had the improvisational "space" sections in your shows. Journeys for people on various journeys. What were some of your visions, or things you saw, or thought of, during these sections? Did Jerry Garcia ever turn into a crab or Gandhi or anything?

[Laughs] Jerry looked like a fish a lot. I wouldn't have visions. Sometimes there were colors. I'd put everything out of my head and be totally in the moment. That part of the show was not about thought, it was just about emotional context. Certainly, people and places take on certain characteristics, especially when you're in the zone. The answer to a question you didn't ask—that you almost asked—is that those parts of the shows, we would never talk about them, afterward or before. We'd never arrange them. They were supposed to be what we were feeling right there at that time.

Or the multiple times happening at that time, in the multiverse. Eleven versions of ourselves living simultaneously in 11 existences. In three, I am breakdancing. Like, I'm a state champion breakdancer. In seven, I live falling in a bottomless pit, with a society of fallers made and arranged to fall. In the last one, I'm a tangerine, or a dolphin.

You have to put them completely out of mind afterward, so you can create something original the next night. That's improvisational art—creating a very sophisticated superstructure, then throwing it away. It shows the impermanence of life. If there are any images for me from these sections, that's it—creating the wonderful mandala, then just blowing it away. Gone forever.

Neil Peart (Rush)

Does your drum set ever seem excessive?

When I added the electronic portion, the kit became 360°. There are a lot of drums. Nothing goes unused though [laughs]. If I had a phobia of small grocery stores, that thing would scare the ever-living shit out of me. Please talk about your book Clockwork Angels. Congrats by the way. You’re getting steampunk there?

There’s some alchemy involved, yes. The book is expanded out from a story I wrote in my lyrics for the album. There’s a watchmaker, who imposes precision. I worked with writer Kevin Anderson, he’s incredible. He took it and ran. We also had Hugh Syme do some art to go with it. He’s won a Juno award, and we’ve worked with him in the past. He’s done tons of art for bands. Were you pissed it took Rush so long to get into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

I’m not too concerned with it.

What about those weird “recommended pages?" I got one for Mistress Gwendolyn last week. She does erotic objectification, like some thing where she makes a coffee table out of herself. I don’t see what’s erotic about being a coffee table. You probably see all kinds of things on tour.

We’re pretty low key actually. We like to stay in our rooms and read. I haven’t seen any coffee tables like that. I was listening to your new song, “The Wreckers." Your words are “The breakers roar, on an unseen shore / In the teeth of a hurricane, we struggle in vain.” Is that about the watchmaker’s steampunk ship?

You probably know more about steampunk than me.

Stay tuned for Parts Two, Three, and Four right here on the KEXP Blog! Trent Moorman is a Seattle-based music writer, and drummer for a ton of local bands, past and present, including Head Like a Kite, Pillar Point, Katie Kate, OCnotes, and many more. You can follow him on Twitter here.

In honor of Funky Drummer Day, local musician and journalist Trent Moorman has graciously shared interviews he's done for The Stranger and Vice Magazine for 24 Drummers, 24 Interviews, a four-part series here on the KEXP Blog!

The station "where the music matters" is paying tribute to the "the only band that matters" this Friday on the air, but the party doesn't stop there: on Saturday, February 6th, The Skylark in West Seattle hosts an International Clash Day Concert to benefit KEXP's New Home! Seattle favorites Polyrhy…